A Day with Robert Morgan, Author of “Boone: A Biography” by Robert Alvin Crum 2025

The image above is a detail of the cover of Boone: A Biography by Robert Morgan. More photos are at the bottom of this article.

NOTE: This article is longer and appeared in the January 2026 issue of the “Compass” magazine published by The Boone Society, Inc. The article is divided into three sections which include (1) a September 2025 event hosted by the NC Daniel Boone Heritage Trail, (2) an interview with Robert Morgan about his Boone biography, and (3) a book review of Boone: A Biography written by Robert Morgan. The magazine article was beautifully laid out by the editors, but since it’s only available to members of The Boone Society and not available on line, I’ve made my article available here. Photos of this event and book covers are found at the bottom.

Beginning of article:

I serve on the Board of the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail. On occasion, and again last Spring, their President, Mary Bolen, called and started with a statement I frequently have heard, “Robert. I have an idea.” Her idea was to hold an event in Wilkesboro, North Carolina at the Wilkes Heritage Museum. She wanted to see if we could have Robert Morgan as a guest speaker to talk about his bestselling book Boone: A Biography. I encouraged her by saying that it sounds like a great idea, and before hanging up, Mary said she was going to further explore this idea.

A short time later, I got another call from Mary Bohlen who used another phrase that I frequently have heard. She said, “Robert. What have I done?” I listened while she advised me that she had contacted Robert Morgan who she said was gracious with her request and outlined what his cost and expenses would be, and a date was set. Mary mentioned that we’ll have to have a Board meeting and asked me to help encourage the Board’s approval and support. I replied that this will be a great event and will be happy to support her. She then added, “I’ve got to go. I have a lot to do.”

The Board of the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail approved and wholeheartedly agreed to support hosting an event with Robert Morgan. This event was set for Saturday afternoon on September 6 at the beautiful Wilkes Heritage Museum in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. It was to be open to the public. All proceeds from ticket sales were to benefit the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail whose mission is to preserve and promote the legacy of Boone’s life in and travel through North Carolina. A fascinating fact to me about the location of this event is that it’s near the Upper Yadkin River by the place where Daniel and Rebecca Boone and most of their extended family settled in 1767. The last of the Boone family left from here in 1779 to move to Kentucky.

When The Boone Society learned about this event, they asked me to write an article about it and include an interview with Robert Morgan with the hopes of publishing it in an issue of the Compass. Of course, I was happy to do so.

The event was set for Saturday, September 6, from 2:00 to 4:00 pm. Premium tickets were sold that included a copy of Morgan’s Boone biography with early admission at two o’clock, so attendees could have their books autographed and an opportunity to pose for a photo with Robert Morgan. Lower price tickets were sold to those that only wanted to attend Robert Morgan’s presentation at three o’clock.

I contacted Robert Morgan and arranged an interview on the morning of this event. He and his wife, Nancy, drove from their home in New York, and stayed the previous evening in a hotel near the Wilkes Heritage Museum. Since there wasn’t a meeting room available at the hotel, we met in the library at the Museum.

We sat down at a conference table with his wife in the room, and my wife was there to take photographs during the interview. I had prepared a set of proposed questions to ask and gave him a copy. I mentioned that my questions were just a guide to help readers learn more about Mr. Morgan’s work, and that I may already know the answer to most of the questions. I was amused by his response, “Never ask a question to which you don’t already know the answer,” which is part of the education attorneys provided me, when I was young.

The questions I asked Mr. Morgan are in bold and italicized type, and the remainder is a summary of our forty-five minute interview. Some of his responses have been shortened to save space in this article, and the interview is as follows:

You primarily write poetry, novels, and short stories. I believe you’ve only written four books that are non-fiction with one being your biography about Daniel Boone and a second which is the sequel Lions of the West. What inspired you to write about Boone?

I’ve always been interested in Boone. My Dad was also very interested in Boone, so he would frequently tell me stories about Daniel Boone. About thirty years ago, I wanted to write a long poem about Daniel Boone, and I began my research back then. I didn't approach this biography completely cold. I had some background. I read Filson’s autobiography. My biography actually got started when my publisher said, “Would you be interested in writing nonfiction books?” And I said, “Well, yes, I’d love to write biography. Maybe I'll write a biography.” And she said, “Well, who would you like to write about?” I suggested either Edgar Allan Poe or Daniel Boone. They checked with their marketing department and decided that a Boone biography would sell better than Poe.

I was very glad they chose Boone. I went on a binge of research and writing, and I’ve never had another period when I was working that intensely. I traveled to Kentucky a dozen times, to the North Carolina Archives, county archives, to Missouri, to the Missouri Historical Society. I was in contact with people like Ted Belue and lots of others. They were all very helpful – including Stephen Aron, and people like Ken Kamper, Neal Hammond, and Kathryn Weiss. They all helped out. I was in touch with all of them. They were generous with their comments. I even went out to see the house built by Nathan in Missouri.

So, it was a kind of binge, and it was glorious. I talked about Boone. I thought about Boone. I read about Boone.

You spent three years researching Boone’s biography. Did you have researchers and/or students assisting with your research?

I didn’t. It was all on my own. I could have used my chair funds to hire a secretary, but I thought I was so deep into this project on my own it'd be hard to train somebody to be of much help. I enjoyed the research. I like research. At some point you have to remind yourself that you’ve got to start writing. The research could go on forever and ever.

I went out to Chicago, to the University of Chicago, the Regenstein Library, where they have the Durrett Collection, and it was fun to be there. They gave me an assistant to go after anything I wanted. When I finally finished up, they said, “By the way, we have funds for a fellowship. Do you want to come back? We'll pay your expenses.”

Well, nobody was using the Durrett Collection. Many Boone scholars don't even know about it. You don’t connect Boone with Chicago. Lincoln maybe. I believe the Durrett family needed money and took the collection from the Filson archives in Louisville and sold it to Chicago after Colonel Durrett’s death.

[When it comes to research], I'm like James Mitchener. He did that incredible amount of research himself. Though he lied and said he had a team, so he wouldn't seem too eccentric, but I think he did it all himself.

Some mistakes can come from using assistants. They may not understand the importance of context in selecting facts or quotes.

In the year 2000, your book Gap Creek was chosen for “Oprah’s Book Club” by Oprah Winfrey. What effect, if any, did this have on your career?

Luckily, I was fifty-five years old at the time and knew it was meaningful, but not terribly. I'd heard of other people who were selected by Oprah who bought yachts and houses in Hawaii and stuff like that. I just kept working every morning as I always had. But what it gave me was so many more readers. Millions of readers. The Oprah Book Club helped sell a lot of books.

It's wonderful to have all those readers. Well, I flew out to San Francisco, when I was on the New York Times Best Seller List. They had a limo and a publicist going with me, and we drove over to Berkeley where I was interviewed for the student paper, and then they took me down to Livermore. Livermore was associated with the atomic bomb, right? Well, we drove up to this shopping plaza, and there was a line of people outside the store, and those with me thought, “What the hell is this?” It was people with books to be signed. So, Oprah had an impact certainly on the sales.

The Boone biography sold out before the book tour. I had no idea how big Daniel Boone was. I wrote the book, and it was thrilling. I started out in Philadelphia. Then in Kansas City and Wichita, there were no books in stores. They already sold out in most of the places. It was wonderful, and it was embarrassing, when people would come to get books, but there were no books available. They printed 25,000 copies, and they just sold out immediately.

You mention in your biography that, “Of major figures in early American history, only Washington and Franklin and Jefferson have had their stories told more often and in greater detail.” Will you please elaborate on why the popularity of Boone’s story being among these other three men?

I discovered this. I did not know it before I wrote the book. Daniel Boone is the first frontiersmen. Boone begins the mystique of frontiersmen in the West, and all the others are derived from him, including Kit Carson, the ultimate scout, who was related to Boone by marriage. There are so many mountain men, cowboys, and other frontier figures, but Boone is the original.

He influenced the Romantic Movement and influenced the way we think about nature. The last chapter of my biography includes quotes from Emerson and Thoreau and Whitman, showing that the type of the frontiersman, not by name, but the type, soon became a part of American culture. The same is true of Crockett; you can find quotes from all three great New England writers that are clearly based on the image of either Boone or Crockett. Whitman actually writes about the Alamo and the Goliad Massacre, but this was a discovery for me. This romantic idea of the West. The forests. The idea of the frontier hero is built around Boone. Byron wrote about him. The Filson biography influenced Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Before Daniel Boone, the wilderness was thought of as a bad place. The forest was evil, a threat. The Indians were there, and it was a place the colonists wanted to clear up. Boone is a figure who loved the wilderness, the mother world of the forest, and loved this middle ground between civilization and the Indians. He's the original. He's at ease with the Indians and with nature. He's friends with the Indians. He doesn't fight the wilderness. He believes in preserving it, even though he's leading people in to clear it up, in effect destroying it. I think he realized that later in life. He’d helped to destroy the hunting ground. But he was almost an Indian himself. He was once adopted by the Shawnees.

In my reading, I believe I saw that you knew you were getting into a very crowded field, when you wrote your biography. Many believe that John Mack Farragher’s biography of Boone published in 1992 is among the best Boone biographies. Your biography was published in 2007. Did you have any thoughts or concerns about “writing in his shadow” or whether there might be a lot of comparisons to his publication?

I believe that Faragher’s biography was among the best. I think there are two or three reasons. He's the first Boone biographer I know who really used the Draper Collection definitively.

He was the first Boone biographer who had that much interest in the Indians and demonstrated a lot of knowledge about them. Faragher was very sensitive about Boone’s relationships with First People, and that puts him very high in my mind.

I think I learned something from each of the previous Boone biographies. What I took most from Faragher’s work was his use of the Draper Collection from the Wisconsin Historical Society. In the nineteenth century Lyman Draper spent his life collecting documents and interviews about the American frontier. His collection is an ocean of papers, some in handwriting almost unreadable. The archive is a treasure trove, and Faragher and others showed me its importance. An interview Draper did with Boone’s son Nathan out in Missouri in 1851 contains much of the essential information we have about the subject.

I found it was important to check every source, every quote. An example would be a letter found in an earlier biography, supposedly a letter written by Boone from Boonesborough in 1775 just as they were building the fort. When I tracked down that letter in Lexington, it was just a typescript, with no original. I should have known it was a fake, because if you know Boone's voice, you would know that Boone doesn’t sound like that. That's not the way he talked. Especially at that time when he’s really trying to build a fort with these people who would not cooperate. They're going out on their own. And that's a very, very tough time. Not only that, but the Indians are also attacking. Boone and his men are living in chaos to some degree. But in the fake letter Boone claims all is going well.

His boss, Richard Henderson, was just staying drunk. There are many incidents where somebody else was officially in charge. But Boone was really in charge. He was the person who had to give the orders. When something had to be done, they turned to him. Everybody looked to him.

Boone just had that leadership ability and was able to use that authority effectively, for example, when Blackfish, in the siege of Boonesborough in 1778, said to Boone that you promised that you're going to surrender the fort. Boone explained he’s no longer in charge – somebody else is in charge. They're very good diplomats – Boone and Blackfish. They're very good actors and good diplomats. Boone was a clever negotiator, and in a way, he learned that from Indians. It was very hard to negotiate with Indians, because they’d claim nobody was in charge. The British or somebody tried to negotiate with the great Chief Attakullakulla. “I'm just Chief of an Overmountain Town, and you know I don't have the authority to do that.” Everybody knew he was in authority.

That, by the way, was passed down to Abraham Lincoln. He was born on the frontier, and he learned that. So, he's in Washington. He's the president. But you know, it's Seward and all these people who ask: “What is your policy? What do you call it?” Lincoln says, “My policy is to have no policy.” Playing that game that Indians and others have played on the frontier. New England educated people didn't know what to do with it. This is one of the ways Indians influenced our culture. There are also many other ways.

The Native American culture was probably a much smarter, better culture in some ways than our own today. They have a lot we could have learned from, but we still have people that won't even consider that, because it's the wrong race. Better leaders inspire us to think that better things are possible. When I was interviewed after the Oprah appearance in 2000, I said, “Good leaders make people feel confident, and bad leaders make them afraid.”

Many writers appear to have periods of time where they struggle to write new material, which is commonly referred to as “writer’s block.” Do you experience this, and, if so, what do you do to get through this?

I don’t have writer’s block, since I write in several genres. It’s a matter of switching back and forth. I’m never at a loss for something to write about. If I hit a block, I begin to work on something else for a while and then later switch back.

Your Boone biography could have ended without your last chapter entitled “Across the River into Legend.” In writing it, you obviously draw on your career as a poet, novelist and English professor. For whatever it’s worth, I believe it’s a beautiful evaluation and analysis of the effect Boone’s life had on writers, painters and poets. Why did you choose to include this as the ending of your biography?

Well, that's Boone’s story continued. These frontier people had an enormous impact on the way the nation thought about itself. I also knew about these authors, had spent years teaching them, reading about them, thinking about them. So, I thought it was something I could do that maybe a lot of other biographers couldn't have done. It's important to the way we think of ourselves to this day: we may be living in the suburbs but really think we’re the kind of people that have a place in the country. We still have a foot in that former world, and, for better or worse, that's what it means to be an American. I keep being surprised by the tenacity of that self-image, national myth. Working on [a book about] Crockett, for instance, and thinking about Walt Whitman. I can see that Walt Whitman is deeply influenced by frontier humor. The hyperbole. The exaggeration. I could imagine Walt Whitman “fighting a barrel of wild cats.” The bragging is like a passage from Huckleberry Finn. “I was weaned on kerosene. My hands are deadly. I can grab the tail of a comet. I can walk the Mississippi on stilts.” Here's Whitman, a high romantic and serious poet clearly taking something from the frontier humor of the Old Southwest. I had never realized that until I was reading about Crockett, who's so closely associated with the humor of the Old Southwest. Here’s Walt Whitman, the great romantic epic poet, but he’s also clearly connected to frontier humor.

Are you going to include this in your book about Crockett?

I certainly am. The last chapter will be very similar to the ending of the Boone biography. I quote Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, plus William Faulkner. Here's the great bear hunter and this mythos that Faulkner talks about. And now the wilderness is going, if not gone. We have this great romantic mythos of the bear hunter. But you would be amazed by what you can find in Ralph Waldo Emerson to echo David Crockett about going to the West. Going to the Southwest, and, of course, Thoreau writes exactly the same thing about exploration, about the ownership of land. I was astonished. I went back and read Walden many times, expecting transcendentalism, and I found these sentences that are so clearly about the frontier mythos. Living at ease with the Indians and the sense of nature and relish in solitude. There's a chapter in Walden called “Solitude.”

I even wove this into a biography of Edgar Allan Poe. Poe’s not just a writer of horror stories. He can write beautifully about nature and solitude in nature. This may be very much disapproved of by some Poe scholars, because they want to see Poe only as a writer of gothic horror. He was an American. He was a rival of Emerson, but he was deeply influenced by Emerson, and the last ten pages of “Eureka” are an essay on cosmology that could easily be a paraphrase of much from Emerson and even more from Walt Whitman. “You want to find God. Look into yourself.” That's exactly what Emerson says in his Divinity School Address. Walt Whitman proclaims, “Turn the priest out. I’m here now.” This is high American Romanticism. Edgar Allan Poe can do it. He can do horror and the poetry of nature. Poe may have the greatest range of any American writer.

Some people, as they get older, consider what their legacy might be. As a University Professor and prolific writer, do you ever consider or reflect on what might be your legacy? If so, are you willing to share it with me?

It’s impossible to know. You have no idea what people will be looking for in fifty years. Twain said immortality is fifty years. Some of my poems might be remembered. The hardest work I've ever spent on writing, and possibly the best, certainly the best expository writing I’ve ever done, is in Boone. When I go back and look at the biography, I say, you know that's not too bad. I put everything I’d learned from writing poetry, texture of words, cadence of sentences, compression of language, and writing fiction, narrative dynamics, character study, tension, and the sense of unfolding story, in the life of Boone. I could not have written Boone: A Biography, had I not written the other books, and earlier essays.

I was very lucky to pick Boone at that time. It was a good period in my career. I was ready to tell the story of Boone. I've never had a period in writing more intense. Gap Creek was intense, but that was like six months or so. A very different kind of writing. I was writing in the voice of the character, an uneducated person. Just hearing that voice is a very different thing from expository writing.

As a creative writer I could do some things other biographers hadn’t done. I imagined Boone making the decision to stay in Kentucky in the second year when logically he would go home and put in a crop for his family. The Boone death scene could be out of a novel yet stays with the facts. Many writers wouldn’t do that. Yet those are the places that readers often enjoy most.

This is the end of my interview.

Once the interview was finished, I thanked Mr. Morgan and gave him two bronze coins with images of Daniel Boone on them. He seemed appreciative. I have in my collection three hardbound copies of his Boone biography, so I took one with me and I asked him to autograph it along with my hardbound copy of his book Lions of the West, which is considered a sequel to his Boone biography. When he asked to whom he should autograph it, I asked for only his autograph. He mentioned that many people don’t want an inscription, because they can resell a book for more with an autograph. I smiled and said that I plan to keep it in my collection, but shared a comment made years ago to me by man of letters, author, and Duke University professor Reynolds Price. When I previously presented to Mr. Price three of his novels for autographs with no inscription, he looked at me and said, “Oh, you’re one of those who wants to make money by reselling autographed books.” I disagreed and still have Price’s novels in my collection.

I then requested a photo of the two of us together, since The Boone Society urged me to do so. We posed in front of a bookcase where I made sure one could see the spine of Robert Morgan’s Boone biography between us.

It was now noon. In order to help his busy day go a little more smoothly, my wife brought in lunch from a nearby restaurant, so Mr. Morgan and I and our wives could enjoy a quiet and private lunch. He continued to discuss his work about Boone but also revealed and discussed additional writing projects on which he was working.

We finished lunch, and at one o’clock, there was a knock on the library door. It was a videographer from “Surry on the Go” indicating he was there to interview Mr. Morgan, so I helped guide him to a corner of the Museum where he could conduct an interview. We said our goodbyes to Nancy Morgan, and my wife and I cleaned up the library table. We proceeded to the second-floor auditorium where there would be a reception for Mr. Morgan, he would autograph books, and his presentation on stage would begin at three o’clock.

It was two o’clock, and premium ticket holders began filing into the auditorium. Tickets were collected at the door in exchange for a paperback copy of Morgan’s Boone: A Biography. It’s now only available in hardback through specialty booksellers. A line formed in front of a table where Mr. Morgan was seated and he signed books, posed for photos and spent time chatting with all who wanted to meet and engage with him. I used my time taking photos, talking to friends and meeting people who were excited to be at this event.

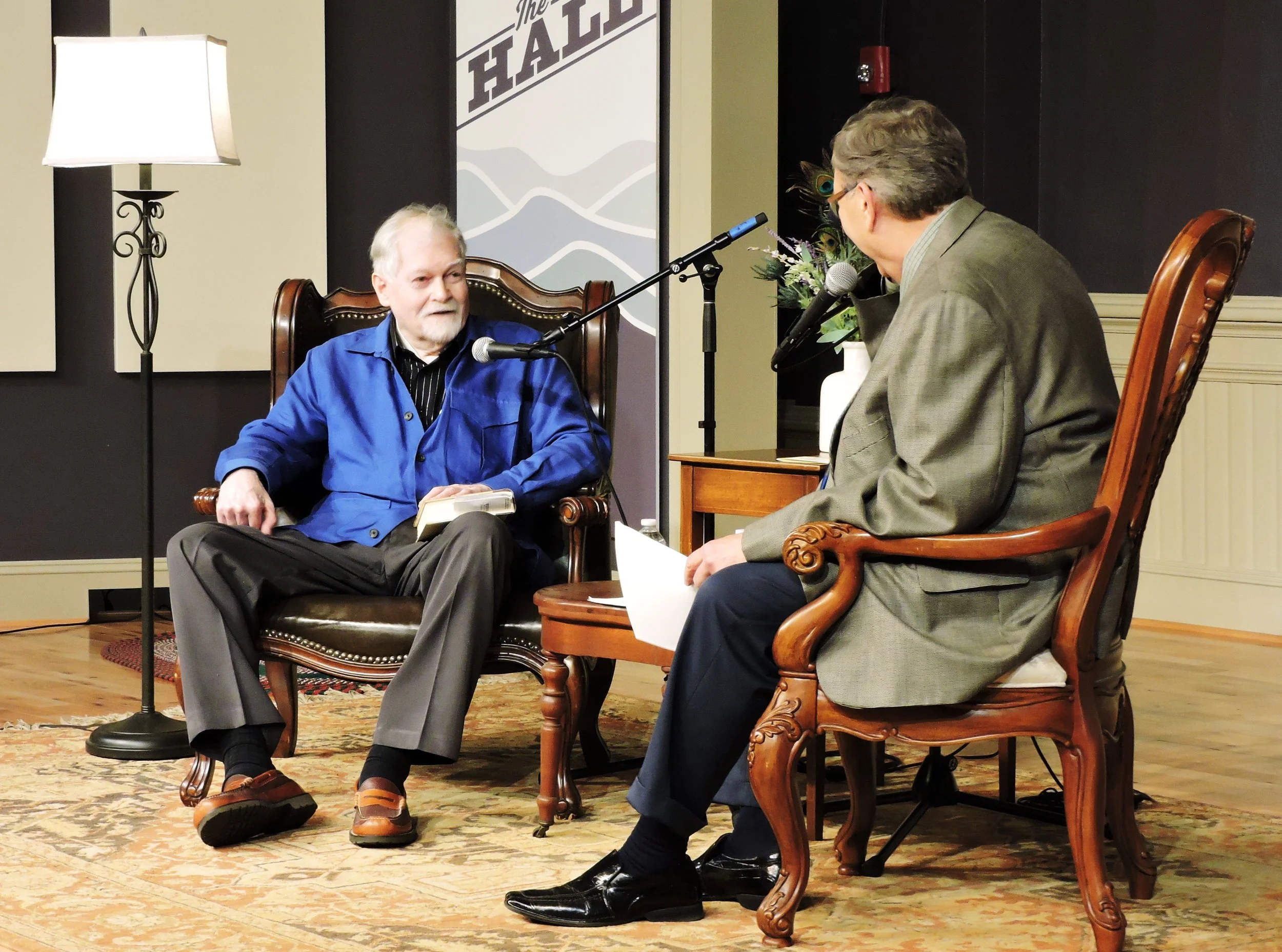

When the appointed hour of three o’clock arrived, people took their seats in a room set up in rows facing the stage. A head count showed there were ninety-two people in the room. I found a seat next to my wife on the right in the first row. We sat there, so I could take notes and come and go with a camera to take photos without disrupting anyone’s view. Mr. Morgan was escorted on stage.

The stage was set with two large comfortable chairs set on an oriental rug. There were two small tables in between the chairs along with a microphone on a stand, and a floor lamp was standing to the right. Mr. Morgan got comfortable in the chair on the left, and Mr. Carl White sat in the chair to our right, and he was planning to interview Mr. Morgan for the next hour.

Mr. White is a broadcaster who hosts the television series Life in the Carolinas. He’s also the creator and host of Life in Wilkes, which is an online series dedicated to the stories of Wilkes County, North Carolina. I took a few more photos and then pulled out my note pad and pen to begin taking notes. In order to not repeat Mr. Morgan’s responses in my interview, the remainder of this article is a summary of Mr. Morgan’s responses to Mr. White’s questions that focus on Daniel Boone.

Morgan used everything he knew about writing to tell the story of Boone, and his background in poetry and storytelling helped him write this biography. When he wrote Brave Enemies: A Novel of the American Revolution in 2003, it led him to writing the biography about Boone. Morgan said about his writing that, “You have to make the reader feel that this story is going somewhere.”

He indicated that Boone’s reputation grew when he was a teenager. He was charismatic and the center of social life. Boone was always seeking the white world but liked being in the wilderness.

While in North Carolina, Boone spent time with the Catawbas and the Cherokee, and he had his foot in two worlds. He learned young not to be too good in a shooting competition with the Indians. Boone understood and had great sympathy toward everyone, including Indians.

North Carolina is where Boone became who he really was. “North Carolina is the place where he became Daniel Boone.” He also really liked Missouri, because the Indians were there. Boone liked whites, the Indians, the wilderness and hunting.

In 1775, Boone wrote a law that there should be “No wanton killing of game.” He understood the destruction of game.

Boone’s character stands up well today, but he was always in debt. This is true of all frontiersmen, because they were all optimists. They had hoped and thought all would go well. We live in a very different world today, but the issues of character are the same.

Boone’s relationship with the Indians was very complicated. Indians define people by likeness, and whites define people by difference.

After Mr. White’s interview, attendees were permitted to come forward to a mic and ask questions. Some of Mr. Morgan’s responses are as follows:

Boone loathed Kentucky after losing everything. He felt betrayed.

I wanted to get a feeling about Who was Daniel Boone? A good teacher of history is a storyteller, and one brings history alive by making it interesting. You’re telling a human story to humans.

The last question was from a young lady who wanted to know how to become a full time professional poet, and Morgan’s response was, “Be persistent. You don’t have to read a specific thing. You have to read everything!”

Boone: A Biography by Robert Morgan- Book review by Robert Alvin Crum copyright 2025

Hardback – Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2007 – 538 pages

ISBN: 978-1-56512-455-4

Paperback – Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008 – 538 pages

ISBN: 978-1-56512-615-2

The publication of this biography is relatively recent, so it’s easy to find it in paperback, and the hardback copy can be found online with some booksellers. It’s included in The Boone Canon due to the high quality of research, analysis of Boone’s life and character, and the style of the author’s prose.

Robert Morgan was born in 1944 in Hendersonville, North Carolina. He spent his childhood on the family farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. As a child, he began writing poetry, fiction and composing music. After beginning to study engineering and mathematics at North Carolina State University, he transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He also changed his course of study to English and graduated in 1965 with a Bachelor of Arts. Morgan then attended University of North Carolina at Greensboro and graduated with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1968.

Initially, Morgan’s publications were short stories, but he quickly switched to writing poetry. When he began teaching at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, he wrote and focused on poetry for ten years. Many prestigious poetry and literary awards followed.

It is also important to look at the Introduction of this book to learn about what led him to write this Boone biography. He was born in the mountains of western North Carolina and spent his time hunting, trapping, fishing, and hiking the mountain trails. During his childhood, Morgan listened to stories about “the old days” while sitting on the porch or in front of the fireplace. He was connected to the past, the Indians, and the early frontier. He writes that his father was a wonderful storyteller who “had a lifelong interest in Daniel Boone and loved to quote the hunter and explorer.” His father also thought that Daniel Boone’s mother, Sarah Morgan, might be related to them. Robert Morgan writes that he “always felt a kinship with the hunter and trapper and scout.”

Much has been written about Boone, and frequently one must wade through what is myth or fact. Morgan works to find what was factual and mentions that Boone is a much more complex person than he noticed before his research. Recently I was blessed with the opportunity to interview Robert Morgan who advised that he spent three years intensely researching this biography. He added that he completed all the research for this book himself, because he loves research, and he did not use any research assistants.

Morgan observes in this biography that, “Of major figures in early American history, only Washington and Franklin and Jefferson have had their stories told more often and in greater detail.” In his research for this book, he explores what it was about Boone “that made him lodge in the memory of all who knew him and made so many want to tell his story.” Morgan wants to know and then shows us how such a common man that was a scout and hunter “turned into an icon of American culture.”

I believe it’s important to know about Morgan’s career as a poet, novelist and English professor to better understand the style and focus of his Boone biography. Morgan uses his vast knowledge of poets and men of letters, especially in his last chapter “Across the River into Legend.” In this closing chapter, he describes Boone’s influence on writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. Morgan shows us how these writers, and even painters, were influenced by Daniel Boone’s life in creating the High Romantic Movement of the nineteenth century.

Morgan’s attention to detail reveals the events of Boone’s story with the accuracy of a historian and a biographer; however, there’s more. Using the prose of the poet that he is, Morgan peels back the many layers of Boone as a complex man to reveal why this “common man” became an American icon.

I highly recommend this book for two reasons. Morgan’s intense research provides an accurate and meticulous biography about Boone. Secondly, his experience and expertise as a poet, novelist and English professor provides a well-written analysis of Boone’s life and personality as the “original frontiersman” who demonstrates, even today, what it means to be an American.

Who Lived on the Bear Creek/Boone Tract? Squire Boone and Son Daniel Never Lived There, So Who Did?

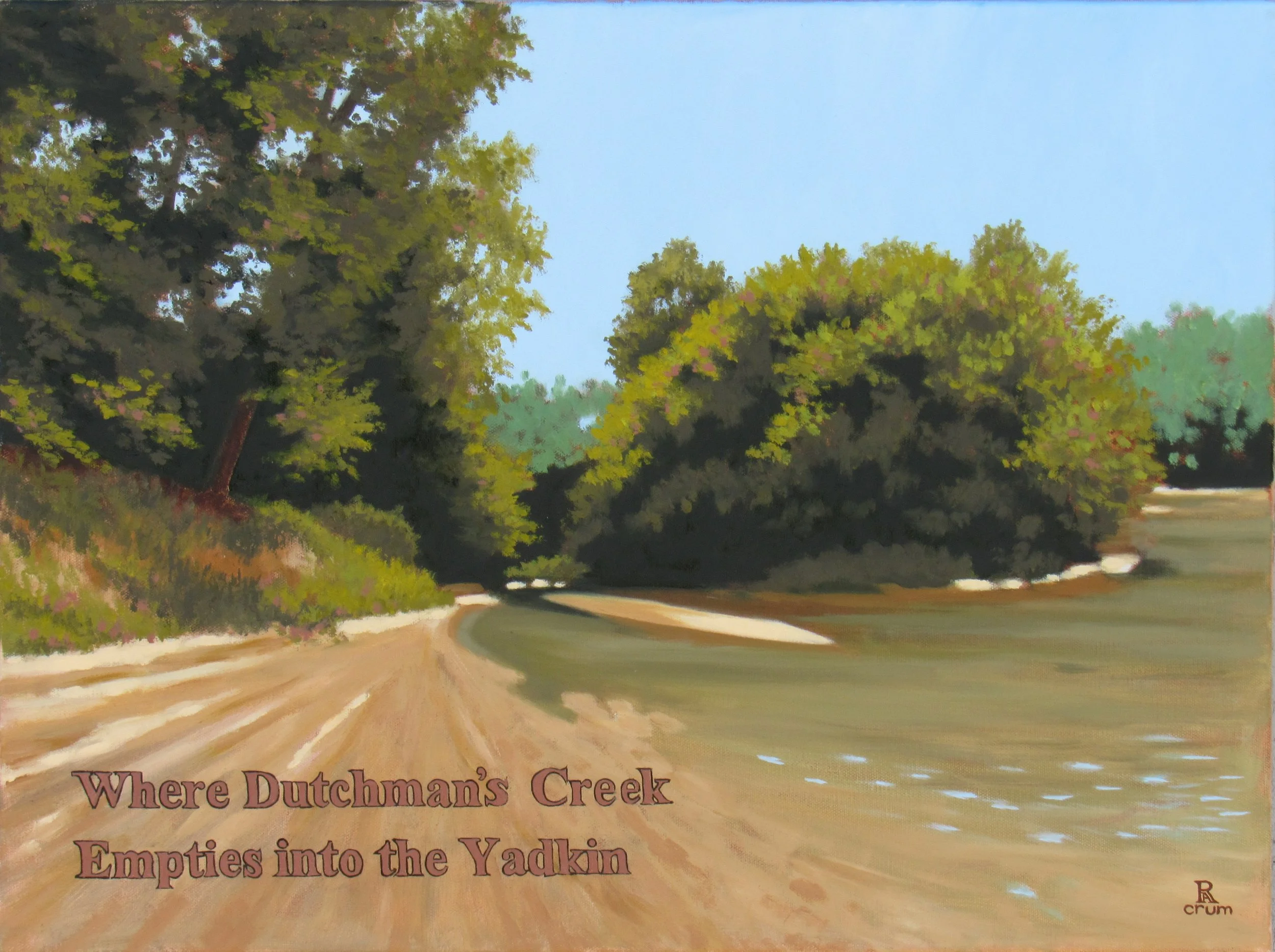

The Shallow Ford on the Yadkin River. Photo by Robert Alvin Crum copyright 2025. More photos are at the end of this article.

Authors, storytellers, and historians frequently say that Squire Boone and his son Daniel lived on Bear Creek which is frequently referred to as the “Boone Tract” in present-day Davie County, North Carolina. However, this is another Boone myth and totally false. So where did Squire and Daniel actually live during their time in North Carolina, and where did this story and misinformation originate? Also, who actually lived there?

In the spring of 1749, Squire Boone traveled from Pennsylvania to North Carolina to explore the area before a possible move. He took with him his son and daughter, Daniel and Elizabeth, and Daniel’s lifelong friend, Henry Miller. They traveled along trails that would later be known as the Great Wagon Road and continued south on a part of the trail known as Morgan Bryan’s Wagon Road that’s between today’s Roanoke, Virginia, and the Shallow Ford on the Yadkin River.

Once they reached the east side of the Shallow Ford, they probably stopped at Edward Hughes’ ordinary (tavern) before crossing the Yadkin River to talk about this new land. Squire knew Edward in Pennsylvania, and their families were connected by siblings’ marriages. Once they crossed the Yadkin, they passed through lands owned by the Bryans (who they also knew in Pennsylvania) and probably also discussed prospective land purchases.

While searching for land, it appears that they camped at a site along the Yadkin River that became known as Boone’s Ford (previously known as Alleman’s Ford). It’s located about six miles north of a place now called “The Point” where the South Yadkin River flows into the North Yadkin River. Just above this location on the east side of the river is a fertile bottom land that became known as Boone’s Bottom, and there was a log structure built on the west side of Boone’s Ford, either at this time or in 1750, that became known as Boone’s Fort.

Finished with their explorations, Squire, Daniel, Elizabeth, and Henry Miller returned to Pennsylvania. On April 11, 1750, Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone sold their 158-acre Exeter Township farm, and on May 1, 1950, they left Pennsylvania for North Carolina. They and their large family followed the same route that they used the previous year during their exploratory trip. Some sources say that the Boones stopped in Winchester, Virginia and may have stayed there for two years. However, Lyman Draper documented that it was a brief stay, and there’s additional evidence supporting Draper.

Documentation showing Squire Boone’s earlier arrival in North Carolina is a land entry in 1750 showing a warrant to measure and lay out 640 acres for Squire Boone lying on Grant’s Creek (alias Lichon Creek) and now known as Elisha Creek. This is frequently referred to as his “Dutchman’s Creek” tract. When this land was surveyed, Squire Boone is named as a “chainer” indicating that he was walking the land long before the grant was issued on April 30, 1753.

Evidence shows the Boones first settled on the east side of the Yadkin where they are shown as living on land adjacent to a survey completed by James Carter dated February 27, 1752. Carter knew the Boones, and his daughter Mary married Jonathan Boone (Daniel’s brother). There’s also documentation in the Draper Manuscripts showing that Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone and their family first lived on the east side of the Yadkin River and near today’s Boone Cave Park. In 1753, they completed the purchase of two separate 640-acre tracts from Lord Granville.

When the large area of Rowan County, North Carolina was formed from Anson County in 1753, Squire Boone became a reasonably prominent colonial official. He served on the first Vestry of the Anglican Parish of St. Luke, was a civil administrator of a large area of Rowan County and was appointed one of the first Justices of the Court of Common Pleas. In the Minutes of the Court of Common Pleas, Squire Boone is listed as one of the Justices, and after his name, it’s recorded that, “Squire Boone’s residence is on the Yadkin at Boone’s Ford.”

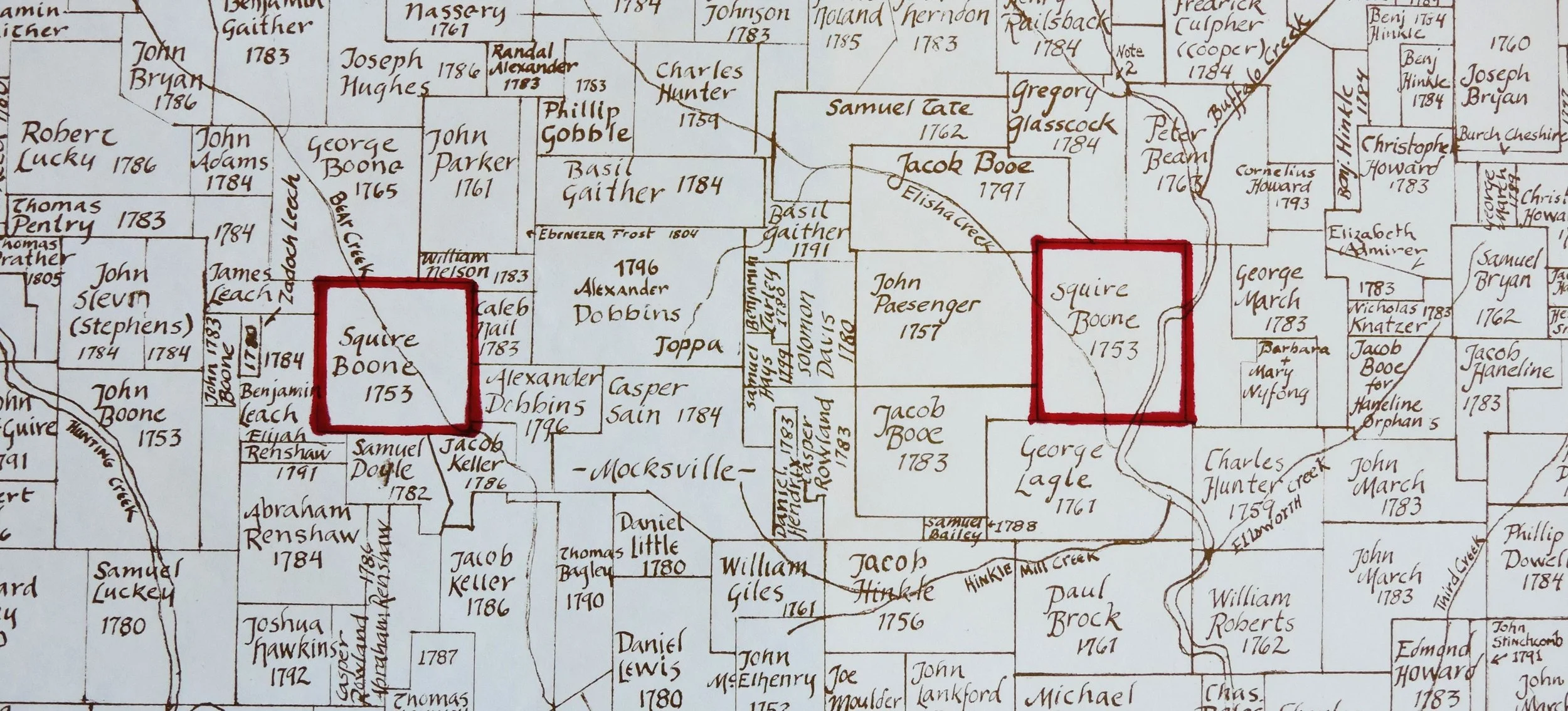

Squire Boone’s purchases of two 640-acre tracts from Lord Granville were finalized in 1753. One is referred to as the Bear Creek or “Boone Tract” (west of present-day Mocksville) and the other is referred to as the “Dutchman’s Creek” tract (east of present-day Mocksville). The following paragraph shows the initial purchase of the Dutchman’s Creek tract by Squire Boone and then the transfer to his son Squire in 1759.

Rowan County Deed Book 3, page 137 shows on April 30, 1753, the “Land granted from Granville to Squire Boone, Esq., of Rowan County, Province of North Carolina, 640 acres land in Parish of (not given) Rowan County, N. C. lying on the South side of Grant’s Creek otherwise Licking Creek. (3 shillings to every 100 acres).” Rowan Deed Book 4, page 196 shows on April 12, 1759, the land gift from “Squire Boone of Rowan County, N. C., and Sarah, his wife, let Squire Boone, Jr., son of said Squire Boone, Sen’r., have for love and affection and for (?) pounds, 640 acres land in Rowan County, lying on South side of Grant’s Creek, otherwise Licking Creek. (This land was granted to Squire Boone, Sen’r., by Granville on April 30th, 1753). Signed Squire Boone and Sarah Boone, Witnesses: Thomas Banfield, Richard Neely and Charles Hunter. Proven, Rowan County Court, October 1759. Let it be registered. Tho’s. Parker, Clerk.”

Squire Boone, Sr. and his family lived on the Dutchman’s Creek tract as verified by a letter dated February 17, 1843, from Daniel Bryan to Lyman Draper. Daniel Bryan writes, “When Dan’l [Boone] was sixteen years old his father Squire Boone Moved to North Carolina and settled on Dutchman’s Creek at the Buffalow Lick, where he died in 1763.” Daniel Bryan was born in 1758 as the second son of William and Mary Boone Bryan. Mary Boone was Daniel Boone’s younger sister, and William Bryan was the uncle of Rebecca Bryan Boone. Daniel Bryan was born at and lived on his parents’ land along the Yadkin River in the Bryan Settlement in North Carolina. He was also the grandson of both Squire Boone, Sr. and Morgan Bryan, Sr. and was also the nephew of Daniel Boone and a first cousin of Rebecca Bryan. This close relationship to the Boones and living nearby as family would make his statements an accurate source about his family and where they lived.

Daniel lived with his parents at the Dutchman’s Creek site until he married Rebecca Bryan, although there are some accounts that Daniel also lived with Morgan Bryan, Rebecca’s uncle, at times before marrying Rebecca. After they were married in 1756, Daniel and Rebecca moved to the Sugar Tree Creek site and lived there until they moved farther up the Yadkin River in 1767.

When Squire and Sarah Boone moved onto the Dutchman Creek tract, who moved onto the Bear Creek or “Boone Tract” when Squire completed that purchase? Review of three legal documents leads one to believe that Israel Boone and his family moved onto and lived at the Bear Creek tract.

It was common for early settlers to establish and operate a tavern or “Public House.” In the records of the Court of Common Pleas for Rowan County, there are two entries in Volume I, pages 43 and 44 on July 11, 1754, involving Israel and Squire Boone with respect to this subject. The first entry shows, “Israil Boon Petitioned this Court for a License to keep Publick House where he Now Lives. Security Proposed James Carter & Squire Boon. Granted.” The second entry says, “Squire Boon Petitioned this Court for A license to keep Public house at his plantation. Security Alexander Osburn & James Carter Esqrs. Granted.” The words for the entry about Israel saying “where he now lives” indicate that he doesn’t own the land, and his father offering security might indicate that Squire is the owner. The second entry for Squire says, “at his own Plantation.” This language indicates that Squire owns the land and is living there, which is at his “Dutchman’s Creek” property.

There’s another legal document that indicates where Israel might have lived. The Rowan County Minutes in January 1765 quote a road overseer as saying, “from the South Yadkin to Israel Boons old Place.” The South Yadkin was just south of the Bear Creek tract where Israel was probably living with his family.

In order to understand the origin of the myth about Squire and his son Daniel living on the Bear Creek tract west of Mocksville, one needs to examine each of the first property sales transactions. The initial deed from Granville to Squire Boone for the 640-acre Bear Creek tract was on December 29, 1753, and is found in Rowan County Deed Book 3, page 164. On October 12, 1759, Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone sold the Bear Creek tract to Daniel and Rebecca Bryan Boone, and this can be found in Rowan County Deed Book 4, pages 195-197. As mentioned above, Daniel and Rebecca never lived here and continued to live at the Sugar Tree Creek site near her Bryan family.

On February 21, 1764, Daniel and Rebecca Bryan Boone sold this 640-acre tract to Aaron Van Cleve as shown in Rowan County Deed Book 4, page 450. Aaron Van Cleve became the father-in-law of Squire Boone, Jr., when he married Aaron’s daughter Jane in 1765. Aaron Van Cleve lived at this Bear Creek tract and sold 200 acres of it to his son Benjamin, and he sold this 200-acre tract in 1782 to John Dick. He lived and farmed here for fourteen years, and when he moved to Wilkes County in 1796, he sold his 200 acres to Jacob Helfer. Jacob farmed this land until his death in 1813 and left the land in his last will and testament to his two sons Davis and Daniel. Daniel changed his last name from Helfer to Helper. In 1817, Daniel married Sarah Brown and farmed this land until his death at the age of 37. His children were born on this farm, and the youngest child born here in 1829 was Hinton Rowan Helper. His mother remarried John Mullican who died in 1876, and she died in 1880. In 1888, Hinton Helper was living in New York City, and he signed a deed to this tract of land conveying any interest he might have in it on July 3, 1888, which can be found in Davie County Deed Book 12, page 255.

What is the origin of this misinformation or myth about Squire and his son Daniel living on the Bear Creek tract west of Mocksville? In the 1800’s historian Lyman Draper gathered volumes of information about early American pioneers.

The myth that Daniel and Squire Boone lived on the Bear Creek tract appears to begin with Hinton Helper, when he wrote Lyman C. Draper in 1883 about the house in which he was born that was located on Squire Boone’s Bear Creek tract. Easier access to the account in the Draper Manuscripts can be found on pages 26 and 27 of James Wall’s History of Davie County, and he mentions at the time he wrote his history that the homesite is that of the late Mr. and Mrs. George Evans. Hinton Helper wrote that, “the ancient logs still solid and visible in the present Evans house might have been part of the original Squire Boone structure.” James Wall adds, “However, such is not the case.” Hinton Helper stated that, “some of the logs from the original Squire Boone house were later used to build a temporary kitchen.”

James Wall continues writing about Helper’s description as follows:

“Helper wrote a very detailed description of the Squire Boone house, standing in ruins, when he was a boy. He states that it was one story, eighteen by twenty-two feet in size, and built of twelve by eighteen-inch face logs. The roof was on a sixty-degree slope, and there was only one door. The entire house, including the roof shingles, was pegged together. The heavy plank door, hung on wooden hinges, had about eighteen handmade nails in it. The floor was of heavy oak boards adzed smooth. Helper says that the chimney was seven feet wide in front and six feet wide behind with a very fireplace and built of soapstone rocks and wood chinks with mud. A smaller log building, twelve by fourteen feet with a hard smooth dirt floor and built of round post oak logs, stood near the house.”

Hinton Helper’s uses his claim about ancient logs being inside the Evans house and a description of a log cabin as his only evidence that Squire and Daniel Boone lived on the Bear Creek or “Boone Tract.” He provides no other evidence. However, Draper was advised in 1843 by Squire’s grandson, who was also a nephew of Daniel Boone and lived near both, that neither Squire nor Daniel lived at Bear Creek. There are documents that suggest Israel Boone lived on the Bear Creek tract, so is it a cabin he built around 1754? Aaron Van Cleve bought this property in 1764and lived there, so is it a cabin he built? Draper apparently didn’t believe Helper either, because when you read his biography about Daniel Boone that was finally published in 1998, he indicates that neither Squire nor Daniel lived on the Bear Creek tract.

Daniel Bryan’s testimony to Lyman Draper was that Squire lived at Dutchman’s Creek until his death and that Daniel Boone lived at Sugar Tree Creek until he moved to the Upper Yadkin. Many writers and historians continue to ignore the evidence that indicates that they didn’t live on the Bear Creek tract. Is this the case of when people repeat an incorrect fact so many times that it ultimately becomes the truth? Apparently this has become so for many telling the stories about the life of Daniel Boone.

West of Mocksville along US Highway 64 (which was once known as Boone’s Road), there are two historical highway signs that mark the property that is the subject of this article. One numbered M-47 with the title “Boone Tract” is just east of the bridge crossing Bear Creek and was installed by the NC Division of Archives and History in 1979. It reads, “In 1753 Lord Granville granted 640 acres on Bear Creek to Squire Boone who sold it in 1759 to his son Daniel. This was a part of the original Boone tract.” The second sign is just a little east of the first. It’s numbered M-33 with the title “Hinton R. Helper” and was installed by the NC Division of Archives and History in 1975. It reads, “Author of The Impending Crisis, a bitterly controversial book which denounced slavery; U.S. Consul at Buenos Aires, 1861-66. Born 150 yds. N.”

Sources:

Abstracts of Court of Common Pleas, Rowan County, North Carolina.

Anson County, North Carolina Deed Records.

Barnhardt, Mike, “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa: Israel Boone Buried Here in 1756,” Davie County Enterprise Record, May 14, 2009, pages 1 & 8.

Belue, Ted Franklin, Editor, The Life of Daniel Boone by Lyman C. Draper, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1998.

Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Acts of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1753, Chapter VII, p. 383.

Draper, Lyman Copeland, Draper Manuscripts, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

Hammond, Neil O., My Father Daniel Boone: The Draper Interviews with Nathan Boone, The University of Kentucky Press, Lexington, Kentucky, 1999.

Kamper, Ken, An Accurate Summary of the Life of Daniel Boone, Daniel Boone History Research – Newsletter No. 6, December 2021.

Kamper, Ken, A Researcher’s Understanding on the Boone Family Move to North Carolina, No. PK17.0211, February 2017.

Linn, Jo White, Abstracts of the Deeds of Rowan County, North Carolina, 1753 – 1785, Books 1 through 10, Salisbury, North Carolina, Privately published, 1983.

Linn, Jo White, Abstracts of the Minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions, Rowan County, North Carolina, Volume I – 1753-1762, Volume II – 1763-1774, Volume III – 1775-1789, Salisbury, North Carolina, Privately published, 1977, 1979, 1982.

Manuscript Collection, The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis, Missouri.

Ramsey, Robert W., Carolina Cradle: Settlement of the Northwest Carolina Frontier 1747-1762, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1964.

Rouse, J.K., North Carolina Picadillo, Kannapolis, North Carolina, 1966.

Rowan County Deeds, Salisbury, North Carolina.

Spraker, Hazel Atterbury, The Boone Family, The Tuttle Company, Rutland, Vermont, 1922.

U.S Quaker Meeting Records 1681-1935.

Wall, James W., Davie County: A Brief History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1976.

Weiss, Kathryn H., Daniel Bryan, Nephew of Daniel Boone: His Narrative and Other Stories, Self-published by Kathryn H. Weiss, 2008.

www.dncr.nc.gov

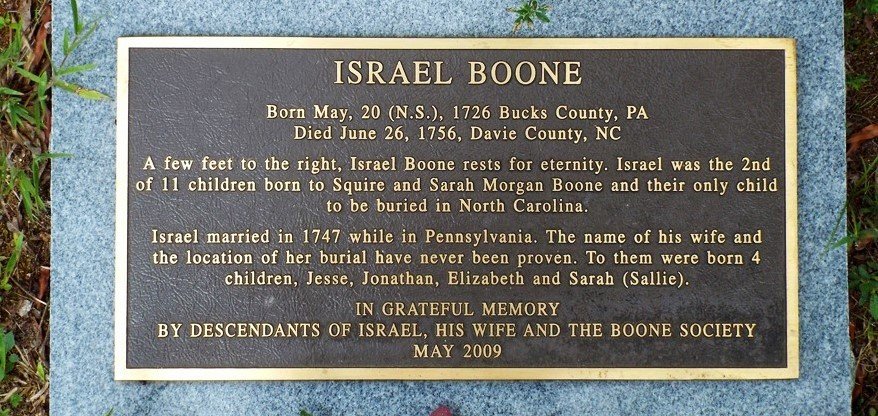

Israel Boone (1726-1756): Daniel Boone’s Brother

Israel Boone’s grave marker at Joppa Cemetery. Photo by RA Crum. More photos can be seen below.

Israel’s father, Squire Boone (1696-1765), was born in Devonshire, England on November 25, 1696. On Christmas Day, he was baptized in the Anglican Church of St. Disen’s in Bradninch, Devon County, England. There’s currently a sign by the American Heritage Trail on the gate leading to the churchyard which says, “Squire Boone, Father of Daniel Boone (1734-1820) the first immortal Western frontiersman, was baptized in this church.” Previously, and at the time Squire was baptized, the church was known as St. Denis or St. Dionysius.

Squire’s parents, George and Mary, were members of this church. Sometime after 1702, George and Mary Boone became members of the Friends Meeting at Cullumpton, since there was no regular Friends Meeting at Bradninch. We commonly refer to the Society of Friends as Quakers. George and Mary’s children would also have become Quakers at this time. There’s a second plaque about the Boones inside St. Disen’s Church which reads as follows:

“Sacred to the memory of the Boone family who emigrated from this parish to America in 1717 and settled in Pennsylvania. Colonel Daniel Boone 1734-1820 of the third generation in America became a great explorer, trail blazer, woodsman and Indian fighter making forays into the new land now known as the State of Kentucky being remembered as the founder of Fort Boonesborough in the new frontier. – This memorial placed here by Boone descendants in America and the Society of Boonesborough, Richmond, Kentucky.”

Squire, his parents, and siblings migrated in 1717 to the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. His future wife Sarah Morgan was born in Pennsylvania in 1700, and her parents were also Quakers. In 1720, Squire Boone married Sarah Morgan in the Gwynedd Meeting (Society of Friends). They had eleven children who were all born in the British Colony of Pennsylvania. Daniel was born as their sixth child, and his oldest brother, Israel, was born on May 20, 1726, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Squire and Sarah’s oldest daughter, Sarah (born June 7, 1724), married a non-Quaker, John Wilcoxson, in 1742 (referred to as marrying a worldling outside the Quaker Meeting). The Society of Friends required Squire to repent for her behavior, which he did, so he could remain a Quaker.

Records of the Exeter Monthly Meeting held on “the 28th Day of the 11th Month of 1747,” states that “Israel Boone, Son of Squire Boone of Exeter, having been Educated and brought up amongst Friends, and as a Member of this Meeting, hath married a Wife who is not in Unity with Friends….” Since Israel, their second child, also married a worldling, Squire was again required to repent for his son’s behavior. When Squire refused, the Society of Friends expelled him from the Friends Meeting, so Squire was no longer a Quaker. However, his wife, Sarah, was able to maintain her standing as a Quaker the rest of her life.

Israel Boone married Martha Farmer in Pennsylvania. Their first child, Jesse (1748-1829), was born in 1748 in Pennsylvania.

Their second child, Jonathan (1750-1826), was born November 3, 1750, in North Carolina. In the Spring of 1750, Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone left Pennsylvania with their children and large extended family. Squire and Sarah Boone and their family (including a nephew) all settled on the east side of the Yadkin River at or near today’s Boone’s Cave Park. It appears that they resided there until they could go through the lengthy process of purchasing land on the west side of the Yadkin River. This required land warrants and surveys before they could finally get a land grant from the Earl of Granville’s land agents. Most of the Boones moved into what is now Davie County except for Samuel Boone and his wife whose land was south of the South Yadkin in what today is Rowan County.

Israel and Martha also had two daughters. Elizabeth (1752-1817) was born on November 28, 1752, in what was still known as Anson County. Her birth was probably on the east side of the Yadkin River at or near today’s Boone’s Cave Park since Israel and family was probably living near his parents until 1753. His father is documented as living there at the time he was first serving in June 1753 as a Rowan County Justice of the Court of Common Pleas.

We have records where most of the Boones purchased land or where they were living. However, there’s no known record of Israel Boone owning land in what is now Davie County. Israel’s father purchased two 640-acre tracts of land. Squire completed on April 30, 1753, the purchase of t tract in eastern Davie County along Grant’s Creek and later referred to Elisha and Dutchman’s Creek. Squire completed on December 29, 1753, the purchase of the tract in western Davie County along Bear Creek (which is frequently referred to as the “Boone Tract”).

There’s great documentation about which land tract Squire and Sarah Boone and their younger children settled. Their grandson, Daniel Bryan, son of William and Mary Boone (Daniel’s sister), wrote a letter to Lyman Draper dated February 17, 1843, advising that, “When Dan’l [Boone] was sixteen years old his father Squire Boone Moved to North Carolina and settled on Dutchman’s Creek at the Buffalo Lick, where he died in 1763.”

If Israel’s parents moved onto the Dutchman Creek tract, then who moved onto the Bear Creek or “Boone Tract” when Squire completed that purchase? Review of three legal documents leads one to believe that Israel and his family moved onto and lived at the Bear Creek tract.

It was common for early settlers to establish and operate a tavern or “Public House.” In the records of the Court of Common Pleas for Rowan County, there are two entries in Volume I, pages 43 and 44 on July 11, 1754, involving Israel and Squire Boone with respect to this subject. The first entry shows, “Israil Boon Petitioned this Court for a License to keep Publick House where he Now Lives. Security Proposed James Carter & Squire Boon. Granted.” The second entry says, “Squire Boon Petitioned this Court for A license to keep Public house at his plantation. Security Alexander Osburn & James Carter Esqrs. Granted.” The words for the entry about Israel saying “where he now lives” indicate that he doesn’t own the land, and his father offering security might indicate that Squire is the owner. The second entry for Squire says, “at his own Plantation.” This language indicates that Squire owns the land and is living there, which is at his “Dutchman Creek” property.

There’s another legal document that indicates where Israel might have lived. The Rowan County Minutes in January 1765 quote a road overseer as saying, “from the South Yadkin to Israel Boons old Place.” The South Yadkin was just south of the Bear Creek Tract where Israel was probably living with his family.

An article dated May 14, 2009, in the Davie County Enterprise Record with the title “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa” quotes Denny Custer, who is a descendant of Israel Boone and at that time was the President of The Boone Society, Inc. He said that he “thinks Israel Boone constructed a cabin on his father’s property west of town.” This is on the Bear Creek or “Boone Tract.”

Israel and Martha’s fourth child, Sarah, was born in 1754. This date would mean that she was born on the Bear Creek tract.

The French & Indian War erupted in 1754, and North Carolina Governor Arthur Dobbs gave his son, Edward Brice Dobbs, a provincial commission as Captain. This son was also a lieutenant in the 7th Royal Fusiliers. As participants in this war, Captain Dobbs was the last to arrive with his North Carolina ranger company at Fort Cumberland on May 30. Daniel Boone was one of the teamsters in Captain Dobbs’ company. When The Battle of the Monongahela began on July 9, 1755, Daniel Boone had crossed the river with his wagon and was huddled in a tight formation with the other waggoners. They were enveloped in the battle, and as they tried to control their teams of horses spooked by musket and canon fire, they realized the British had lost the battle to the French. Boone and the other waggoners cut their harnesses from their horses and escaped from what would have been certain death.

Daniel Boone returned from the battle to North Carolina during the summer of 1755 to find that Israel Boone was suffering from the disease known then as consumption. Today, we refer to this disease as tuberculosis. Another disease that afflicted both settlers and Natives in North Carolina was smallpox. Daniel survived this disease as a child that left his face scarred for life. As mentioned in a previous article, in 1738, the Cherokee suffered from a smallpox epidemic that killed half of their population, and in 1759, a smallpox epidemic killed half of the Catawba Nation.

The Boones settled in what today is Davie County on the west side of the Yadkin River. East of them on the other side of the Yadkin was the Wachovia Tract where the Moravians established in 1753 a small community they called Bethabara, which means “house of passage.” Fifteen Moravians from Pennsylvania first settled this village. It became a bustling trade center but was only intended to be used until Salem could be established. When that occurred in 1766, many of the Moravian settlers moved to Salem.

It was well-known that the Moravians could treat the ill and those afflicted with disease. Therefore, it wasn’t unusual that in 1755 Sarah Morgan Boone took her son Israel to Bethabara and left him for treatment of consumption. In the Moravian Records the Bethabara Diary dated 1755 states that on August 26, “A consumptive came with his mother, and asked to remain two weeks for treatment, and we could not refuse. We lodged him in the old house.”

There’s another entry in the 1755 Bethabara Diary which states on September 1, “The consumptive was taken home by his brother, who came for him last evening. He, - Mr. Boone, - returned on the 6th, accompanied by his father, who remained overnight. On the 15th his brother came for him once more, and he left, there being small hope of his recovery.” A few weeks later, his father and brother (probably Daniel) spent the night to see Israel and took him home, when the doctor said there was little hope for recovery.

The “sick house” and the “stranger’s house” have been reconstructed at Bethabara Historic Park. They are believed to be the locations where the Boone’s stayed when here in 1755.

Lyman Draper interviewed a Samuel Boone who said that Israel died on June 26, 1756, and was buried near present-day Mocksville. Draper also wrote that Israel had two sons and two daughters and that the daughters contracted consumption from their mother and died at an early age. After Israel’s death, the two sons, Jesse and Jonathan, were cared for and raised by Daniel and Rebecca Boone.

It appears the information that the two daughters contracted consumption and died is incorrect. Tradition says that their mother died before their father and was probably buried at Burying Ground Ridge, although there’s no documentation for this. Both daughters survived, later married, and moved to Kentucky.

In the previously mentioned article dated May 14, 2009 with the interview of Denny Custer, he mentioned, “It is a curious point that none of the children of Israel and [his] wife, nor any other of the Squire and Sarah Boone family contracted consumption from Israel or his wife.” This is possibly due to the fact that Israel and his family were living in a more isolated setting and away from the remainder of the Boone family while living on the Bear Creek tract.

Originally known as Burying Ground Ridge, the area around today’s Joppa Cemetery was settled in the early 1750’s. The cemetery is believed to hold the graves of many of those early settlers. For many years, it was believed that the oldest marked grave in Joppa Cemetery (Burying Ground Ridge) was that of Squire Boone (1696-1765).

In October 2005, Katherine Weiss wrote an article about Israel Boone’s possible burial location. In it, she quotes letters from Lyman Draper’s Boone Series written by James Williamson and Jethro Rumple. There’s an analysis of a broken stone that was next to the gravestone of Squire Boone, and the broken stone is very similar to Squire’s. Text on the broken stone was ++BoonE and part of a number 5 and then a 6. The conclusion is that the only family member that died in 1756 and would have had stone similar to his father was Israel.

After research to confirm the location of the grave of Israel Boone, his descendants and The Boone Society, Inc. placed a bronze plaque in Joppa Cemetery in May 2009 marking Israel’s grave to the left of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. The text on the plaque marking his grave reads as follows:

ISRAEL BOONE

Born May 20 (N.S.), 1726 Bucks County, PA

Died June 26, 1756, Davie County, NC

A few feet to the right, Israel Boone rests for eternity. Israel was the 2nd

Of 11 children born to Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone and their only child

to be buried in North Carolina.

Israel married in 1747 while in Pennsylvania. The name of his wife and

the location of her burial have never been proven. To them were born 4

Children, Jesse, Jonathan, Elizabeth, and Sarah (Sallie).

IN GRATEFUL MEMORY

BY DESCENDANTS OF ISRAEL, HIS WIFE AND THE BOONE SOCIETY

MAY 2009

Sources:

Abstracts of Court of Common Pleas, Rowan County, North Carolina.

Anson County, North Carolina Deed Records.

Barnhardt, Mike, “Science Meets History: Radar Used to study Below the Surface at Joppa Cemetery,” Davie County Enterprise Record, June 25, 2009.

Barnhardt, Mike, “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa: Israel Boone Buried Here in 1756,” Davie County Enterprise Record, May 14, 2009, pages 1 & 8.

Belue, Ted Franklin, Editor, The Life of Daniel Boone by Lyman C. Draper, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1998.

Boone, Alice H., Descendants of Israel Boone, McCann Printing & Litho Co., Springfield, Missouri, 1969.

Colonial and State Records of North Carolina.

Draper, Lyman Copeland, Draper Manuscripts, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

Faragher, John Mack, Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer, Henry Holt and Company, Inc., New York, New York, 1992.

findagrave.com/memorial/8117530/Israel-boone.

Fries, Adelaide Lisetta, Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, 1752-1771, Vol. 1, Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, State Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina, Reprinted 1968.

historicbethabara.org.

Linn, Jo White, Abstracts of the Deeds of Rowan County, North Carolina, 1753 – 1785, Books 1 through 10, Salisbury, North Carolina, Privately published, 1983.

Linn, Jo White, Abstracts of the Minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions, Rowan County, North Carolina, Volume I – 1753-1762, Volume II – 1763-1774, Volume III – 1775-1789, Salisbury, North Carolina, Privately published, 1977, 1979, 1982.

“Marker at Israel Boone’s Grave to be Dedicated: Daniel’s Less Famous Brother Died Here on June 26, 1756,” Davie County Enterprise Record, Mocksville, North Carolina, April 30, 2009, page 4.

Preston, David L., Braddock’s Defeat: the Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2015.

Ramsey, Robert W., Carolina Cradle: Settlement of the Northwest Carolina Frontier 1747-1762, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1964.

Rowan County Deeds, Salisbury, North Carolina.

Rumple, Rev. Jethro, A History of Rowan County, North Carolina: Containing Sketches of Prominent Families and Distinguished Men, Published by J.J. Bruner, Salisbury, North Carolina, 1881.

Spraker, Hazel Atterbury, The Boone Family, The Tuttle Company, Rutland, Vermont, 1922.

U.S. Quaker Meeting Records 1681 – 1935.

Van Noppen, Ina Woestemeyer and John James, Daniel Boone, Backswoodsman: The Green Woods Were His Portion, The Appalachian Press, Boone, North Carolina, 1966.

Wall, James W., History of Davie County in the Forks of the Yadkin, Davie Historical Publishing Association, Mocksville, North Carolina, 1969.

Wall, James W., Martin, Flossie, and Boone, Howell, The Squire, Daniel, and John Boone Families in Davie County, North Carolina, Davie County Printing Company, Mocksville, North Carolina, 1982.

Weiss, Katherine, “Israel Boone’s Burial,” Compass, The Boone Society, Inc., October 2005, page 11.

www.stdisens.org.uk/history

A Brief History of Joppa Cemetery (Burying Ground Ridge)

Graves at right of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Wilcoxson graves are at left foreground. Photo by Robert Alvin Crum copyright 2024. More images below.

Joppa Cemetery has become a popular historical destination for visitors to Mocksville. It is located at 908 Yadkinville Road on the east side of U.S. Highway 601 North in Mocksville, North Carolina. Location coordinates are N35.90914; W80.57750.

The area around today’s Joppa Cemetery was first settled by European migrants in the late 1740’s and early 1750’s. It was originally known as Burying Ground Ridge. In my travels in Europe, I observed that the term “cemetery” was less common, and these places are still frequently called “burying grounds.” Joppa Cemetery holds the graves of many of those early settlers and is considered the oldest cemetery in Davie County.

Until this century, what was considered the earliest marked grave in Joppa Cemetery was that of Squire Boone, who was buried there in 1765. Squire’s wife, Sarah, died in 1777 and was buried beside him. A bronze plaque mounted above their gravestones quotes the text on each of their stones. Squire’s text recites, “Squire Boone departed this life they sixty-ninth year of his age in thay year of our Lord 1765 Geneiary tha 2.” The text on Sarah’s stone is simpler and says, “Sah + Boone departed this life aged 77 years.”

In October 2005, Katherine Weiss wrote an article about Israel Boone’s possible burial location that was published in The Boone Society’s publication the Compass. In it she quotes letters written by James Williamson and Jethro Rumple found in Lyman Draper’s Boone Series. There’s an analysis of a broken stone that was next to the gravestone of Squire Boone, and the broken stone is very similar to Squire’s. Text on the broken stone was ++BoonE and part of a number 5 and then a 6. The conclusion is that the only family member that died in 1756 and would have had a stone similar to his father was Israel.

Once research confirmed the location of the grave of Israel Boone, his descendants and The Boone Society, Inc. placed a bronze plaque in Joppa Cemetery in May 2009 marking Israel’s grave just to the left of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. There are two newspaper articles about this event published by the Davie County Enterprise Record. The one announcing this event was published on April 30, 2009, with the title “Marker at Israel Boone’s Grave to be Dedicated: Daniel’s Less Famous Brother Died Here on June 26, 1756.” A follow up article was published on May 14, 2009, after the installation and dedication of Israel’s new gave marker with the title “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa: Israel Boone Buried Here in 1756.”

In between Israel Boone’s grave marker at left and Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone’s gravestones at right is a large bronze plaque mounted on top of a brick base. It’s referred to as “The Boone Family in Davie County Marker.” Historian James Wall wrote a paragraph about this that can be found in the Martin-Wall History Room at the Davie County Public Library in Mocksville. This paragraph reads as follows:

“The large plaque locating the six Boone families house sites in Davie County was placed there by the late Howell Boone (1922-1988) on the 250th anniversary of Daniel Boone’s birth [1984]. Howell was a descendant of John Boone, Squire Boone’s nephew, who first lived near Hunting Creek and later moved his log house to Boone Farm Road near and behind Center United Methodist Church. Howell Boone came from New York and in retirement lived on his ancestor’s land grant for some ten years. He worked extensively in the Davie County Library researching Boone information, assisting people with general research, speaking to groups, and traveling to Boone family sites in several states.”

I mentioned that the bronze plaque is mounted on a brick base. The first time I visited Joppa Cemetery years ago, I noticed to the right of this bronze plaque is a higher brick structure and encased in it are the gravestones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. I researched the reason for the encasement. I have already mentioned research that shows documentation of Israel Boone’s gravestone that was still in Joppa Cemetery in the late 19th century. Further into this chapter, I also mention additional gravestones documented as being in Joppa Cemetery during the 19th century that later disappeared.

Concern and recognition of gravestones disappearing was demonstrated by the actions of Dr. James McGuire (1829-1906) who wanted to preserve the gravestones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Dr. McGuire was concerned about both stones being in danger of vandalism, theft, or chipping by treasure hunters. He removed their stones from the cemetery and put them in a bank vault for safekeeping at the Bank of Davie, which had recently opened in 1901. Dr. McGuire also drove large iron pipes into the ground to mark the two graves, and this can be seen in an older photograph.

Historian James Wall writes that in the 1920’s Squire and Sarah Boone’s gravestones were removed from the bank vault, returned to the cemetery, and encased in a concrete structure to protect them. There are old photos that show this structure. This old encasement was mostly rock held together with a small amount of concrete, so it continued to be damaged by the weather that included rain and ice, and the stones were still subject to possible theft and vandalism.

In 1972, local historian and preservationist Hugh Larew insisted on replacing this encasement and gave James Wall permission to construct a new encasement for Squire and Sarah Boone’s gravestones using Mr. Larew’s design. In 1972, Jane McGuire provided brick for the encasement from her homeplace built in the mid-1800’s and was located on Jericho Road near Bear Creek. An instructor in brick laying at Davie High School, Henry Crotts, and one of his students (David Miller?) laid the brick. James Wall and his son held the two gravestones in place while the brick was set in place. Hugh Larew installed the copper cover on top, and James Wall purchased the bronze plaque with the original text on the gravestones and had it bolted to the face of the brick encasement.

John Boone (1727-1803), Squire’s nephew, lived and owned land just to the west of Joppa Cemetery and the location is on Boone Farm Road which intersects with U.S. Highway 64. He died in 1803 and is documented as being buried near the grave of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Until at least the 1880’s, his tombstone was documented as being “alongside” the tombstones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Beal Ijames wrote Lyman Draper in 1884 advising him that John Boone is buried in Joppa Cemetery. There was another letter to Lyman Draper in 1887 written by Hinton H. Helper saying that John Boone’s soapstone headstone at Joppa Cemetery could not be read. His gravestone, like so many in this cemetery, later disappeared.

Squire’s oldest daughter, Sarah, married John Wilcoxson, and he is also documented as being buried near Squire and Sarah Boone. Squire Boone, Jr.'s in-laws, Aaron and Rachel Van Cleve are also documented as being buried in Joppa Cemetery. New granite gravestones were installed in 2025 along with SAR granite Patriot markers by the Col. Daniel Boone Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution for John Boone, Aaron Van Cleve, and John Wilcoxson.

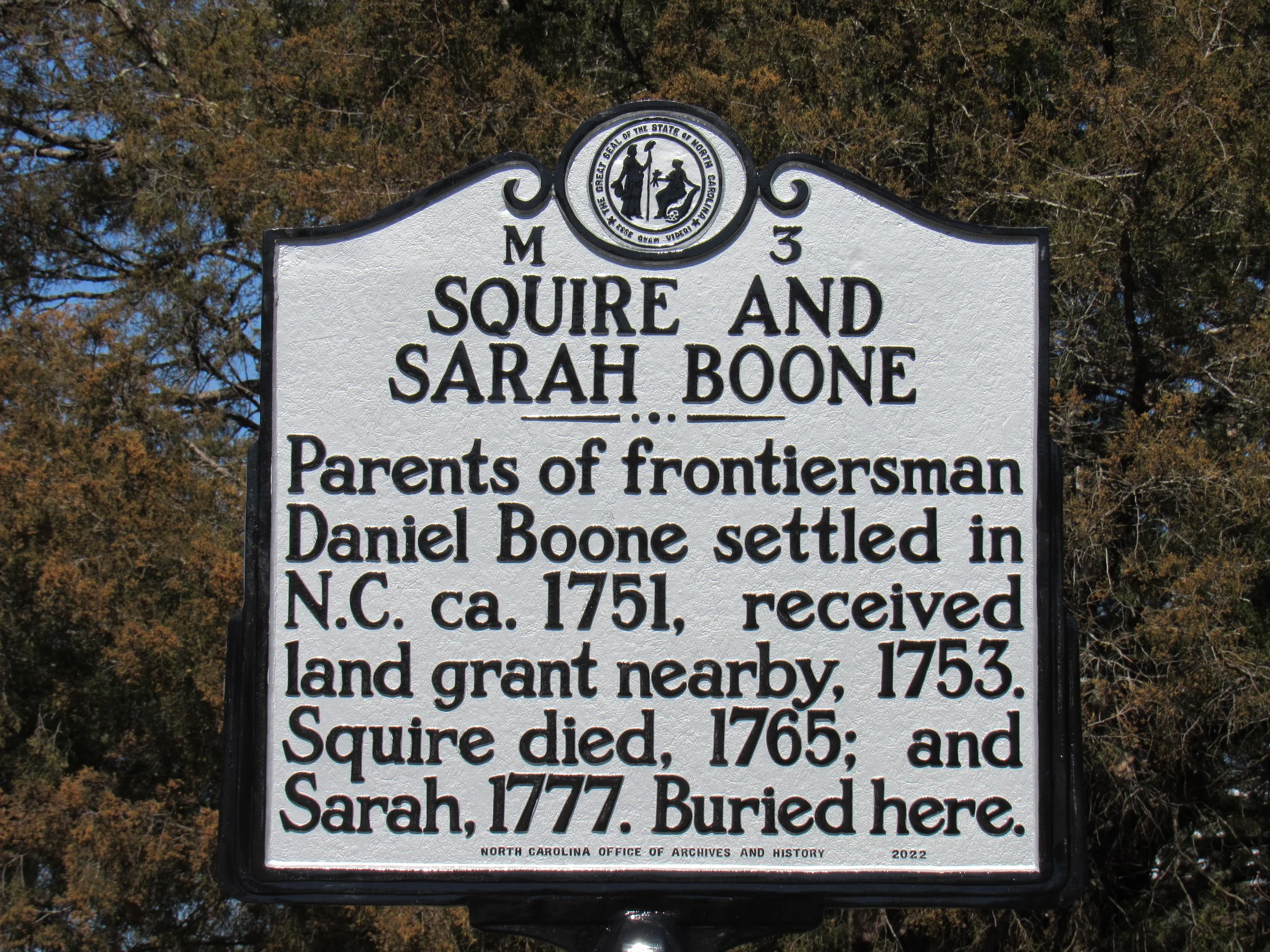

I dwell on the Boone graves, because many, including historians, believe that numerous people have worked to preserve this cemetery as the final resting place of the parents of Daniel Boone. In 1938, North Carolina Highway Marker M 3 was first installed here which said, “DANIEL BOONE’S PARENTS – Squire and Sarah Boone are buried here. Daniel Boone, 1734 – 1820, lived many years in this region.”

In 2020, I was putting together a tour of Boone sites in North Carolina for The Boone Society. When at Joppa Cemetery, I noticed that the Boone highway sign needed painting and repair, so I contacted the State to see if they could do maintenance work on it. They advised me that they would have to replace it due to its age and advised that they would keep the old sign. I also made some solicitations to help fund the replacement of the sign.

In 2022, the new historic highway sign at the front of the cemetery was set in the same location. It now reads, “SQUIRE AND SARAH BOONE – Parents of frontiersman Daniel Boone settled in N.C. ca. 1751, received land grant nearby, 1753. Squire died, 1765, and Sarah, 1777. Buried here.”

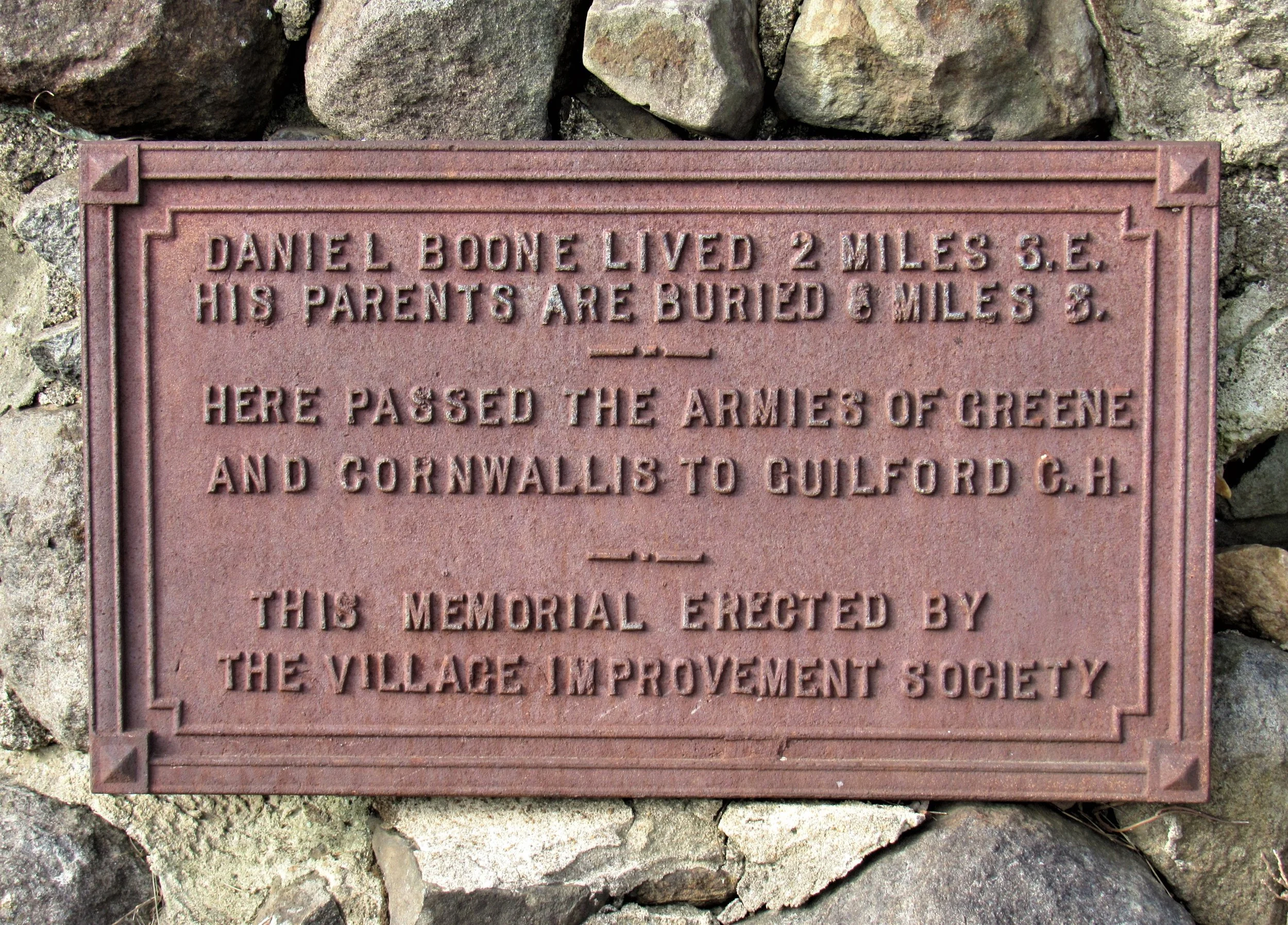

There’s another marker in Davie County that refers to Joppa as the site where Squire and Sarah Boone are buried. In northeastern Davie County is the village of Farmington, and there you’ll find a small monument on the southwest corner of the intersection of Farmington Road and NC Highway 801. The Village Improvement Society erected this memorial structure. It is constructed with stacked stones, and on the face of it is a Hampton Rich “Boone Trail Highway” plaque. Below that is another plaque, and the text on the first line says, “Daniel Boone lived 2 miles S.E. [Sugar Tree Creek] His parents are buried 8 miles S. [Joppa Cemetery].”

In addition to the Boone family association, this cemetery is connected to the Presbyterian congregation originally located here. The first known building at Joppa Cemetery was a small, one-room, log meeting house. Historian James Wall wrote that it’s believed to have been in the southeast corner of the cemetery just inside today’s old stone wall marking the original cemetery. (It was actually in the southwest corner as explained below.) First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville traces its founding to this place.

The May 1767 minutes of the Synod of Philadelphia and New York first mention a group of worshipers at the meeting house in Joppa Cemetery. It was a log building. There’s speculation that a congregation was meeting here as early as January 1765, when Squire Boone was buried in the nearby cemetery. The May 1789, Presbyterian Church records refer to the church name for the first time as Joppa, which is a Biblical word meaning beautiful.

In 1792, the congregation received its first permanent pastor, the Reverend J. D. Kilpatrick. A frame church building was built and replaced the original log church in the same location in 1793. The Reverend Samuel Milton Frost, who attended Sunday School as a boy in the Joppa church, later confirmed this in a letter he wrote in 1899 to T. B. Bailey with a description of the church. He recalled it being a framed church with a door at each end, there was a high pulpit with narrow steps, and the backs of the pews were very high.

The church was without a pastor for thirty years and was served irregularly by itinerant ministers and catechists. In November 1827, the Rev. William A. Hall came to serve Joppa and Unity churches.

There’s a large wooden cross in the cemetery that is maintained by First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville, and, annually, they conduct an Easter Sunrise Service at this location. This cross is in front of the gravestone of Joannah Smith who died and was buried here in 1827. In front of her gravestone is a bronze plaque which was more recently installed, and it reads as follows:

“In 1827 Joanna Smith bequeathed $600 so her Church could have a pastor. The unparalleled generosity of dedicated Presbyterians Joannah and husband James Smith, enabled Joppa Presbyterian Church, then located at this site, to call the Rev. William A. Hall as pastor. Without these gifts, Joppa Church might have closed.

The Joppa church members moved from this country church into the town of Mocksville around 1834, and it subsequently became the First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville. The growing community and Rev. Hall’s energetic leadership from 1827-1851 resulted in rapid growth and progress for the church.”

In 1951, the Presbyterian Church deeded the cemetery to Joppa Cemetery, Inc. who is still the owner. There are many unmarked graves in the old part of the cemetery surrounded by a stone wall. In this area, there are six known and marked Revolutionary War Patriot graves whose names are John Boone, Evan Ellis, Basil Gaither, Isaac Jones, Aaron Van Cleve and John Wilcoxson. There are at least seven graves of Civil War veterans in this area. Quite a few veteran graves are also located in the front and newer part of the cemetery.

Historian Mark Hager is a past professor at Lenoir-Rhyne University and President of the Forks of the Yadkin and Davie County History Museum. He and his students have frequently done maintenance and research at Joppa Cemetery. On June 25, 2009, the newspaper Davie County Enterprise Record published an article “Science Meets History: Radar Used to study Below the Surface at Joppa Cemetery.” This article reports that Hager and his students received help with this project from the Wake Forest University Archeology Department. “Ken Robinson was at Joppa this month with ground-penetrating radar to try to locate where the Joppa Church stood or any unmarked graves.” In 2025, I contacted the Archeology Department at Wake Forest University to find a report about this project, and they responded that they have no record of this project being conducted by them. I then researched this for a record at Lenoir-Rhyne University and found no record.