A Brief History of Joppa Cemetery (Burying Ground Ridge)

Joppa Cemetery has become a popular historical destination for visitors to Mocksville. It is located at 908 Yadkinville Road on the east side of U.S. Highway 601 North in Mocksville, North Carolina. Location coordinates are N35.90914; W80.57750.

The area around today’s Joppa Cemetery was first settled by European migrants in the late 1740’s and early 1750’s. It was originally known as Burying Ground Ridge. In my travels in Europe, I observed that the term “cemetery” was less common, and these places are still frequently called “burying grounds.” Joppa Cemetery holds the graves of many of those early settlers and is considered the oldest cemetery in Davie County.

Until this century, what was considered the earliest marked grave in Joppa Cemetery was that of Squire Boone, who was buried there in 1765. Squire’s wife, Sarah, died in 1777 and was buried beside him. A bronze plaque mounted above their gravestones quotes the text on each of their stones. Squire’s text recites, “Squire Boone departed this life they sixty-ninth year of his age in thay year of our Lord 1765 Geneiary tha 2.” The text on Sarah’s stone is simpler and says, “Sah + Boone departed this life aged 77 years.”

In October 2005, Katherine Weiss wrote an article about Israel Boone’s possible burial location that was published in The Boone Society’s publication the Compass. In it she quotes letters written by James Williamson and Jethro Rumple found in Lyman Draper’s Boone Series. There’s an analysis of a broken stone that was next to the gravestone of Squire Boone, and the broken stone is very similar to Squire’s. Text on the broken stone was ++BoonE and part of a number 5 and then a 6. The conclusion is that the only family member that died in 1756 and would have had a stone similar to his father was Israel.

Once research confirmed the location of the grave of Israel Boone, his descendants and The Boone Society, Inc. placed a bronze plaque in Joppa Cemetery in May 2009 marking Israel’s grave just to the left of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. There are two newspaper articles about this event published by the Davie County Enterprise Record. The one announcing this event was published on April 30, 2009, with the title “Marker at Israel Boone’s Grave to be Dedicated: Daniel’s Less Famous Brother Died Here on June 26, 1756.” A follow up article was published on May 14, 2009, after the installation and dedication of Israel’s new gave marker with the title “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa: Israel Boone Buried Here in 1756.”

In between Israel Boone’s grave marker at left and Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone’s gravestones at right is a large bronze plaque mounted on top of a brick base. It’s referred to as “The Boone Family in Davie County Marker.” Historian James Wall wrote a paragraph about this that can be found in the Martin-Wall History Room at the Davie County Public Library in Mocksville. This paragraph reads as follows:

“The large plaque locating the six Boone families house sites in Davie County was placed there by the late Howell Boone (1922-1988) on the 250th anniversary of Daniel Boone’s birth [1984]. Howell was a descendant of John Boone, Squire Boone’s nephew, who first lived near Hunting Creek and later moved his log house to Boone Farm Road near and behind Center United Methodist Church. Howell Boone came from New York and in retirement lived on his ancestor’s land grant for some ten years. He worked extensively in the Davie County Library researching Boone information, assisting people with general research, speaking to groups, and traveling to Boone family sites in several states.”

I mentioned that the bronze plaque is mounted on a brick base. The first time I visited Joppa Cemetery years ago, I noticed to the right of this bronze plaque is a higher brick structure and encased in it are the gravestones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. I researched the reason for the encasement. I have already mentioned research that shows documentation of Israel Boone’s gravestone that was still in Joppa Cemetery in the late 19th century. Further into this chapter, I also mention additional gravestones documented as being in Joppa Cemetery during the 19th century that later disappeared.

Concern and recognition of gravestones disappearing was demonstrated by the actions of Dr. James McGuire (1829-1906) who wanted to preserve the gravestones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Dr. McGuire was concerned about both stones being in danger of vandalism, theft, or chipping by treasure hunters. He removed their stones from the cemetery and put them in a bank vault for safekeeping at the Bank of Davie, which had recently opened in 1901. Dr. McGuire also drove large iron pipes into the ground to mark the two graves, and this can be seen in an older photograph.

Historian James Wall writes that in the 1920’s Squire and Sarah Boone’s gravestones were removed from the bank vault, returned to the cemetery, and encased in a concrete structure to protect them. There are old photos that show this structure. This old encasement was mostly rock held together with a small amount of concrete, so it continued to be damaged by the weather that included rain and ice, and the stones were still subject to possible theft and vandalism.

In 1972, local historian and preservationist Hugh Larew insisted on replacing this encasement and gave James Wall permission to construct a new encasement for Squire and Sarah Boone’s gravestones using Mr. Larew’s design. In 1972, Jane McGuire provided brick for the encasement from her homeplace built in the mid-1800’s and was located on Jericho Road near Bear Creek. An instructor in brick laying at Davie High School, Henry Crotts, and one of his students (David Miller?) laid the brick. James Wall and his son held the two gravestones in place while the brick was set in place. Hugh Larew installed the copper cover on top, and James Wall purchased the bronze plaque with the original text on the gravestones and had it bolted to the face of the brick encasement.

John Boone (1727-1803), Squire’s nephew, lived and owned land just to the west of Joppa Cemetery and the location is on Boone Farm Road which intersects with U.S. Highway 64. He died in 1803 and is documented as being buried near the grave of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Until at least the 1880’s, his tombstone was documented as being “alongside” the tombstones of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone. Beal Ijames wrote Lyman Draper in 1884 advising him that John Boone is buried in Joppa Cemetery. There was another letter to Lyman Draper in 1887 written by Hinton H. Helper saying that John Boone’s soapstone headstone at Joppa Cemetery could not be read. His gravestone, like so many in this cemetery, later disappeared.

Squire’s oldest daughter, Sarah, married John Wilcoxson, and he is also documented as being buried near Squire and Sarah Boone. Squire Boone, Jr.'s in-laws, Aaron and Rachel Van Cleve are also documented as being buried in Joppa Cemetery. New granite gravestones were installed in 2025 along with SAR granite Patriot markers by the Col. Daniel Boone Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution for John Boone, Aaron Van Cleve, and John Wilcoxson.

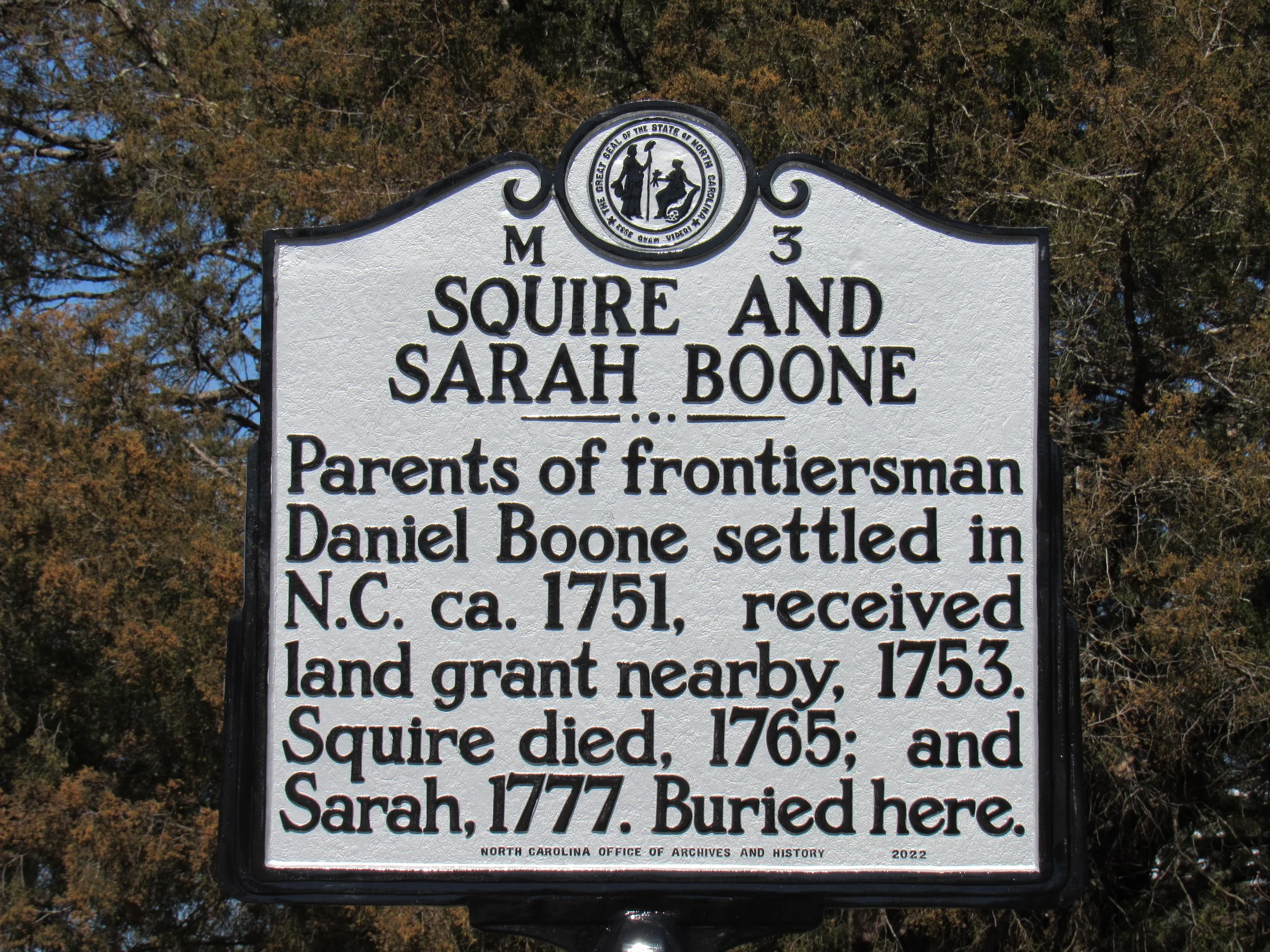

I dwell on the Boone graves, because many, including historians, believe that numerous people have worked to preserve this cemetery as the final resting place of the parents of Daniel Boone. In 1938, North Carolina Highway Marker M 3 was first installed here which said, “DANIEL BOONE’S PARENTS – Squire and Sarah Boone are buried here. Daniel Boone, 1734 – 1820, lived many years in this region.”

In 2020, I was putting together a tour of Boone sites in North Carolina for The Boone Society. When at Joppa Cemetery, I noticed that the Boone highway sign needed painting and repair, so I contacted the State to see if they could do maintenance work on it. They advised me that they would have to replace it due to its age and advised that they would keep the old sign. I also made some solicitations to help fund the replacement of the sign.

In 2022, the new historic highway sign at the front of the cemetery was set in the same location. It now reads, “SQUIRE AND SARAH BOONE – Parents of frontiersman Daniel Boone settled in N.C. ca. 1751, received land grant nearby, 1753. Squire died, 1765, and Sarah, 1777. Buried here.”

There’s another marker in Davie County that refers to Joppa as the site where Squire and Sarah Boone are buried. In northeastern Davie County is the village of Farmington, and there you’ll find a small monument on the southwest corner of the intersection of Farmington Road and NC Highway 801. The Village Improvement Society erected this memorial structure. It is constructed with stacked stones, and on the face of it is a Hampton Rich “Boone Trail Highway” plaque. Below that is another plaque, and the text on the first line says, “Daniel Boone lived 2 miles S.E. [Sugar Tree Creek] His parents are buried 8 miles S. [Joppa Cemetery].”

In addition to the Boone family association, this cemetery is connected to the Presbyterian congregation originally located here. The first known building at Joppa Cemetery was a small, one-room, log meeting house. Historian James Wall wrote that it’s believed to have been in the southeast corner of the cemetery just inside today’s old stone wall marking the original cemetery. (It was actually in the southwest corner as explained below.) First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville traces its founding to this place.

The May 1767 minutes of the Synod of Philadelphia and New York first mention a group of worshipers at the meeting house in Joppa Cemetery. It was a log building. There’s speculation that a congregation was meeting here as early as January 1765, when Squire Boone was buried in the nearby cemetery. The May 1789, Presbyterian Church records refer to the church name for the first time as Joppa, which is a Biblical word meaning beautiful.

In 1792, the congregation received its first permanent pastor, the Reverend J. D. Kilpatrick. A frame church building was built and replaced the original log church in the same location in 1793. The Reverend Samuel Milton Frost, who attended Sunday School as a boy in the Joppa church, later confirmed this in a letter he wrote in 1899 to T. B. Bailey with a description of the church. He recalled it being a framed church with a door at each end, there was a high pulpit with narrow steps, and the backs of the pews were very high.

The church was without a pastor for thirty years and was served irregularly by itinerant ministers and catechists. In November 1827, the Rev. William A. Hall came to serve Joppa and Unity churches.

There’s a large wooden cross in the cemetery that is maintained by First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville, and, annually, they conduct an Easter Sunrise Service at this location. This cross is in front of the gravestone of Joannah Smith who died and was buried here in 1827. In front of her gravestone is a bronze plaque which was more recently installed, and it reads as follows:

“In 1827 Joanna Smith bequeathed $600 so her Church could have a pastor. The unparalleled generosity of dedicated Presbyterians Joannah and husband James Smith, enabled Joppa Presbyterian Church, then located at this site, to call the Rev. William A. Hall as pastor. Without these gifts, Joppa Church might have closed.

The Joppa church members moved from this country church into the town of Mocksville around 1834, and it subsequently became the First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville. The growing community and Rev. Hall’s energetic leadership from 1827-1851 resulted in rapid growth and progress for the church.”

In 1951, the Presbyterian Church deeded the cemetery to Joppa Cemetery, Inc. who is still the owner. There are many unmarked graves in the old part of the cemetery surrounded by a stone wall. In this area, there are six known and marked Revolutionary War Patriot graves whose names are John Boone, Evan Ellis, Basil Gaither, Isaac Jones, Aaron Van Cleve and John Wilcoxson. There are at least seven graves of Civil War veterans in this area. Quite a few veteran graves are also located in the front and newer part of the cemetery.

Historian Mark Hager is a past professor at Lenoir-Rhyne University and President of the Forks of the Yadkin and Davie County History Museum. He and his students have frequently done maintenance and research at Joppa Cemetery. On June 25, 2009, the newspaper Davie County Enterprise Record published an article “Science Meets History: Radar Used to study Below the Surface at Joppa Cemetery.” This article reports that Hager and his students received help with this project from the Wake Forest University Archeology Department. “Ken Robinson was at Joppa this month with ground-penetrating radar to try to locate where the Joppa Church stood or any unmarked graves.” In 2025, I contacted the Archeology Department at Wake Forest University to find a report about this project, and they responded that they have no record of this project being conducted by them. I then researched this for a record at Lenoir-Rhyne University and found no record.

Since I found no record at either University, I placed a phone call to Historian Mark Hager and had a one-hour conversation with him. He didn’t have the report readily available, so he explained the findings of the study. Historian James Wall previously wrote that Joppa Church built in the late 1700’s was located in the southeast corner of the old part of the cemetery surrounded by stone which is to the back right as you walk through the iron gates. However, the study found that Joppa Church was in the southwest corner of the old part of the cemetery which is at the front right as you walk through the iron gates. The conclusion is that James Wall had his compass settings pointing in the wrong direction, so he mentioned that Joppa Church was in the southeast corner rather than the southwest corner where it actually stood. There were some graves with stones found in the area where the church once stood, and it was concluded that the burials were after the time the church disappeared, which was in the 1830’s.

Another important finding confirmed by this ground-penetrating radar study in 2009 is the location of graves of enslaved people. It was determined that slaves were buried in the northwest corner of the old part of the cemetery which is to the front left as you enter through the iron gates. In that area, the study found many graves, but no gravestones above nor below ground. When the enslaved were buried, oak slabs were used, but no stones were used as grave markers. The wooden slabs have long since deteriorated over time. These unmarked graves were found within the old stone cemetery wall and just north or to the left of Joppa Church. I found this a little fascinating, because I’ve observed at other old cemeteries that the enslaved were usually buried outside the walls or fencing surrounding the cemetery or around the perimeter. Mark Hager recommended that one read M. Ruth Little’s book Sticks and Stones: Three Centuries of North Carolina Gravemarkers. In this book, she illustrates and explains how wood rather than stone was used to mark the graves of the enslaved.

Now I’d like to return to the historic significance of this cemetery that was established around 1750. At that time, funerals and weddings were occasions that drew large crowds. James S. Brawley mentions on pages 57 and 58 of his book The Rowan Story 1753-1973 the following:

“Funerals were public affairs and among the most important social functions. Private burials were illegal, and every planter was required to ‘set apart a Burial Place and fence the same for interring of all Christian Persons whether Bond or Free that shall die on their plantations.’ Considerable publicity was given to the burial of the dead. Invitations were sent to relatives and friends and there was an abundance of things to eat and drink for the entertainment of the guests.”

Given this background, it’s easy to imagine the large number of people and historical figures that visited and were in Joppa Cemetery for a social gathering in its early years, when it was still known as “Burying Ground Ridge.” Consider as an example the death of Squire Boone in 1765. At his funeral would have been his family, other close families, and Rowan County government officials. You can easily determine that one or more hundred could have been there. Squire and Sarah had ten children, and all would have been present except Israel, who died in 1756, and Squire was buried beside him. Eight of his ten children had married by then and would have had their children with them. Three of their children (Daniel, Mary, and Martha) had married into the Bryan family. Other Bryans had worked with and were associated with the Boones, so their families would have attended this event. George Boone married into the Linville family, and Jonathan Boone married into the Carter family, so these well-known families also would have been at this funeral. Squire served in three positions in Rowan County’s colonial government that included the prominent position of Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. Therefore, many past and present government officials were probably there on that day. Many people in attendance later migrated west and became famous. Two examples are Squire Boone, Jr., and his brother Daniel, who became an American icon.

Daniel Boone last visited his mother Sarah Morgan Boone in 1773. He was close to her, especially as a child in Pennsylvania, and it’s well-known that he cried when he left knowing it was probably the last time he’d see her. It was. When her husband Squire died, Sarah went to live with her daughter Mary who was married to William Bryan. Sarah died in 1777 and was buried next to her husband. Her son Daniel returned to North Carolina in the Fall of 1778 and lived only a few miles from his parents’ graves until September 1779. He spent the year hunting the area and is documented as traveling to the nearby town of Salem and to the City of Charleston, South Carolina. I think it’s highly likely that he would have wandered into Joppa Cemetery to visit his parents’ graves, especially since his mother had just died the previous year, when he was absent.

Squire Boone’s funeral is only one example of what would have been a large public affair and social event in this place. Many others occurred involving prominent local, colonial and, later, state officials and businessmen who were laid to rest in this place.

It’s also interesting to note that many of those buried here are not surrounded by graves of their numerous children and grandchildren due to a very important event. At the beginning of the American Revolution and again in 1779, many of the children and grandchildren of those buried here were led by Daniel Boone out of this area of North Carolina and through the Cumberland Gap during America’s first great westward expansion. Among them were the descendants of Squire and Sarah Morgan Boone, John Boone, Aaron Van Cleve, and John Wilcoxson, and the names of the families following Daniel Boone were the Boones, Bryans, Grants, Hays, Hunts, Linvilles, Van Cleves, Wilcoxsons and many more.

I’ve focused on the connection to the Boones and that of Revolutionary War Patriots buried in Joppa Cemetery. However, this is a historical cemetery that was established over 275 years ago and is still an active cemetery. Many of the local and prominent families that have lived nearby for centuries are also buried here. Some examples are P. F. Meroney, a nephew of Thomas Jefferson, Marshall Bell, a surgeon in the Confederate army, Thomas and Rufus Brown, heirs to the Brown and Brown tobacco fortune which became R.J. Reynolds, and many more. A volume could be written about the lives and souls of so many buried here, but I’ll have to leave that to others.

As cemeteries go, Joppa is a smaller cemetery when compared to most, since it’s only about 50 yards wide by approximately 150 yards deep. A narrow blacktop drive leads back to an ancient, iron gate that serves as an entrance to the old section surrounded by the stone-stacked walls. The blacktop drive also curves back to the highway to allow additional access. Towering oaks, hickory, maples, and cedars shade this site during the warmer months and help soften the highway sounds drifting from the front of the property. Wandering through this quiet place provides both a sense of history and spiritual peace.

Sources:

Barnhardt, Mike, “Science Meets History: Radar Used to study Below the Surface at Joppa Cemetery,” Davie County Enterprise Record, June 25, 2009.

Barnhardt, Mike, “There’s a New Oldest Grave at Joppa: Israel Boone Buried Here in 1756,” Davie County Enterprise Record, May 14, 2009, pages 1 & 8.

Brawley, James S., The Rowan Story 1753-1953: A Narrative History of Rowan County, North Carolina, Rowan Printing Company, Salisbury, North Carolina, 1953.

Cemetery Census, Davie County North Carolina Cemeteries, Davie County Historical & Genealogical Society, http://cemeterycensus.com/nc/davie/cem089.htm

Daughters of the American Revolution, www.dar.org/library/onlineresearch/ancestorsearch.

Davie County Register of Deeds, Mocksville, NC.

Draper, Lyman Copeland, Draper Manuscripts, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, WI.

Heitman, Mary J., History of Joppa Church, Martin-Wall History Room, Davie Public Library, Mocksville, NC.

Little, M. Ruth, Sticks and Stones: Three Centuries of North Carolina Gravemarkers, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapell Hill & London, 1998.

“Marker at Israel Boone’s Grave to be Dedicated: Daniel’s Less Famous Brother Died Here on June 26, 1756,” Davie County Enterprise Record, April 30, 2009.

Martin-Wall History Room, Davie County Public Library, Mocksville, NC.

North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh, NC, www.ncmarkers.com.

Rowan County Register of Deeds, Salisbury, NC.

Sons of the American Revolution, www.sarpatriots.org/patriots search and cemetery search.

Spraker, Hazel Atterbury, The Boone Family, The Tuttle Company, Rutland, Vermont, 1922.

State of North Carolina, Department of Revenue, Raleigh, North Carolina.

U.S. Quaker Meeting Records 1681-1935.

Wall, James W., A History of the First Presbyterian Church of Mocksville, North Carolina, Mocksville, NC,1963.

Wall, James W., History of Davie County, Davie County Historical Publishing Association, Mocksville, North Carolina, 1969.

Weiss, Katherine, “Israel Boone’s Burial,” Compass, The Boone Society, Inc., October 2005, Volume 9, Issue 4, page 11.