A Day with Robert Morgan, Author of “Boone: A Biography” by Robert Alvin Crum 2025

NOTE: This article is longer and appeared in the January 2026 issue of the “Compass” magazine published by The Boone Society, Inc. The article is divided into three sections which include (1) a September 2025 event hosted by the NC Daniel Boone Heritage Trail, (2) an interview with Robert Morgan about his Boone biography, and (3) a book review of Boone: A Biography written by Robert Morgan. The magazine article was beautifully laid out by the editors, but since it’s only available to members of The Boone Society and not available on line, I’ve made my article available here. Photos of this event and book covers are found at the bottom.

Beginning of article:

I serve on the Board of the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail. On occasion, and again last Spring, their President, Mary Bolen, called and started with a statement I frequently have heard, “Robert. I have an idea.” Her idea was to hold an event in Wilkesboro, North Carolina at the Wilkes Heritage Museum. She wanted to see if we could have Robert Morgan as a guest speaker to talk about his bestselling book Boone: A Biography. I encouraged her by saying that it sounds like a great idea, and before hanging up, Mary said she was going to further explore this idea.

A short time later, I got another call from Mary Bohlen who used another phrase that I frequently have heard. She said, “Robert. What have I done?” I listened while she advised me that she had contacted Robert Morgan who she said was gracious with her request and outlined what his cost and expenses would be, and a date was set. Mary mentioned that we’ll have to have a Board meeting and asked me to help encourage the Board’s approval and support. I replied that this will be a great event and will be happy to support her. She then added, “I’ve got to go. I have a lot to do.”

The Board of the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail approved and wholeheartedly agreed to support hosting an event with Robert Morgan. This event was set for Saturday afternoon on September 6 at the beautiful Wilkes Heritage Museum in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. It was to be open to the public. All proceeds from ticket sales were to benefit the North Carolina Daniel Boone Heritage Trail whose mission is to preserve and promote the legacy of Boone’s life in and travel through North Carolina. A fascinating fact to me about the location of this event is that it’s near the Upper Yadkin River by the place where Daniel and Rebecca Boone and most of their extended family settled in 1767. The last of the Boone family left from here in 1779 to move to Kentucky.

When The Boone Society learned about this event, they asked me to write an article about it and include an interview with Robert Morgan with the hopes of publishing it in an issue of the Compass. Of course, I was happy to do so.

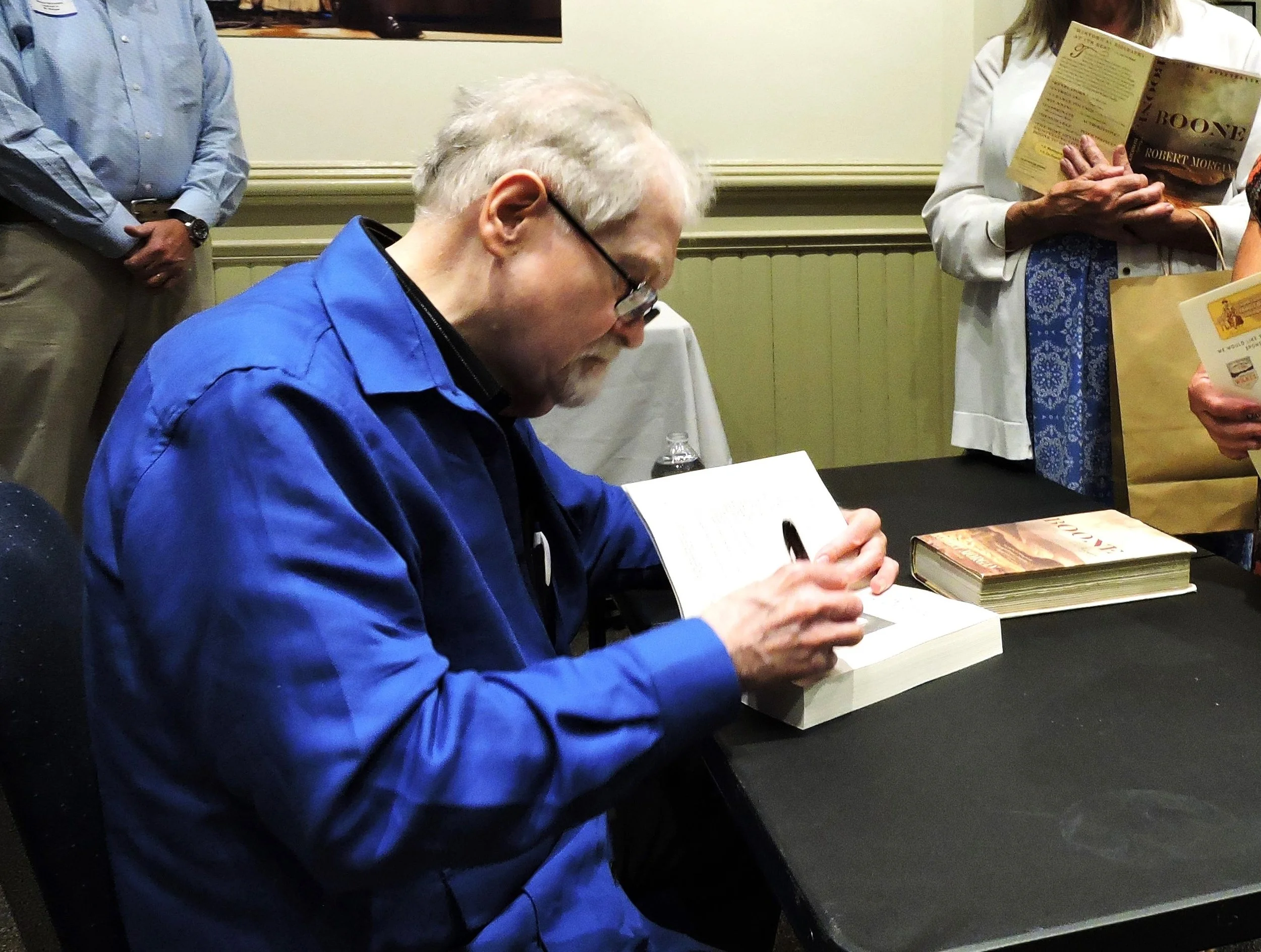

The event was set for Saturday, September 6, from 2:00 to 4:00 pm. Premium tickets were sold that included a copy of Morgan’s Boone biography with early admission at two o’clock, so attendees could have their books autographed and an opportunity to pose for a photo with Robert Morgan. Lower price tickets were sold to those that only wanted to attend Robert Morgan’s presentation at three o’clock.

I contacted Robert Morgan and arranged an interview on the morning of this event. He and his wife, Nancy, drove from their home in New York, and stayed the previous evening in a hotel near the Wilkes Heritage Museum. Since there wasn’t a meeting room available at the hotel, we met in the library at the Museum.

We sat down at a conference table with his wife in the room, and my wife was there to take photographs during the interview. I had prepared a set of proposed questions to ask and gave him a copy. I mentioned that my questions were just a guide to help readers learn more about Mr. Morgan’s work, and that I may already know the answer to most of the questions. I was amused by his response, “Never ask a question to which you don’t already know the answer,” which is part of the education attorneys provided me, when I was young.

The questions I asked Mr. Morgan are in bold and italicized type, and the remainder is a summary of our forty-five minute interview. Some of his responses have been shortened to save space in this article, and the interview is as follows:

You primarily write poetry, novels, and short stories. I believe you’ve only written four books that are non-fiction with one being your biography about Daniel Boone and a second which is the sequel Lions of the West. What inspired you to write about Boone?

I’ve always been interested in Boone. My Dad was also very interested in Boone, so he would frequently tell me stories about Daniel Boone. About thirty years ago, I wanted to write a long poem about Daniel Boone, and I began my research back then. I didn't approach this biography completely cold. I had some background. I read Filson’s autobiography. My biography actually got started when my publisher said, “Would you be interested in writing nonfiction books?” And I said, “Well, yes, I’d love to write biography. Maybe I'll write a biography.” And she said, “Well, who would you like to write about?” I suggested either Edgar Allan Poe or Daniel Boone. They checked with their marketing department and decided that a Boone biography would sell better than Poe.

I was very glad they chose Boone. I went on a binge of research and writing, and I’ve never had another period when I was working that intensely. I traveled to Kentucky a dozen times, to the North Carolina Archives, county archives, to Missouri, to the Missouri Historical Society. I was in contact with people like Ted Belue and lots of others. They were all very helpful – including Stephen Aron, and people like Ken Kamper, Neal Hammond, and Kathryn Weiss. They all helped out. I was in touch with all of them. They were generous with their comments. I even went out to see the house built by Nathan in Missouri.

So, it was a kind of binge, and it was glorious. I talked about Boone. I thought about Boone. I read about Boone.

You spent three years researching Boone’s biography. Did you have researchers and/or students assisting with your research?

I didn’t. It was all on my own. I could have used my chair funds to hire a secretary, but I thought I was so deep into this project on my own it'd be hard to train somebody to be of much help. I enjoyed the research. I like research. At some point you have to remind yourself that you’ve got to start writing. The research could go on forever and ever.

I went out to Chicago, to the University of Chicago, the Regenstein Library, where they have the Durrett Collection, and it was fun to be there. They gave me an assistant to go after anything I wanted. When I finally finished up, they said, “By the way, we have funds for a fellowship. Do you want to come back? We'll pay your expenses.”

Well, nobody was using the Durrett Collection. Many Boone scholars don't even know about it. You don’t connect Boone with Chicago. Lincoln maybe. I believe the Durrett family needed money and took the collection from the Filson archives in Louisville and sold it to Chicago after Colonel Durrett’s death.

[When it comes to research], I'm like James Mitchener. He did that incredible amount of research himself. Though he lied and said he had a team, so he wouldn't seem too eccentric, but I think he did it all himself.

Some mistakes can come from using assistants. They may not understand the importance of context in selecting facts or quotes.

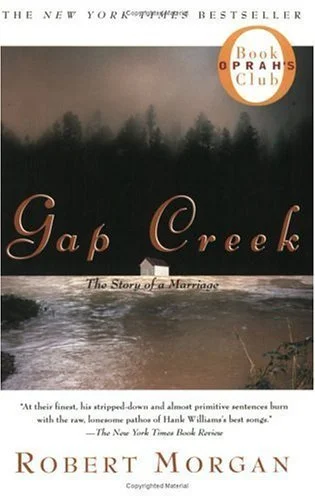

In the year 2000, your book Gap Creek was chosen for “Oprah’s Book Club” by Oprah Winfrey. What effect, if any, did this have on your career?

Luckily, I was fifty-five years old at the time and knew it was meaningful, but not terribly. I'd heard of other people who were selected by Oprah who bought yachts and houses in Hawaii and stuff like that. I just kept working every morning as I always had. But what it gave me was so many more readers. Millions of readers. The Oprah Book Club helped sell a lot of books.

It's wonderful to have all those readers. Well, I flew out to San Francisco, when I was on the New York Times Best Seller List. They had a limo and a publicist going with me, and we drove over to Berkeley where I was interviewed for the student paper, and then they took me down to Livermore. Livermore was associated with the atomic bomb, right? Well, we drove up to this shopping plaza, and there was a line of people outside the store, and those with me thought, “What the hell is this?” It was people with books to be signed. So, Oprah had an impact certainly on the sales.

The Boone biography sold out before the book tour. I had no idea how big Daniel Boone was. I wrote the book, and it was thrilling. I started out in Philadelphia. Then in Kansas City and Wichita, there were no books in stores. They already sold out in most of the places. It was wonderful, and it was embarrassing, when people would come to get books, but there were no books available. They printed 25,000 copies, and they just sold out immediately.

You mention in your biography that, “Of major figures in early American history, only Washington and Franklin and Jefferson have had their stories told more often and in greater detail.” Will you please elaborate on why the popularity of Boone’s story being among these other three men?

I discovered this. I did not know it before I wrote the book. Daniel Boone is the first frontiersmen. Boone begins the mystique of frontiersmen in the West, and all the others are derived from him, including Kit Carson, the ultimate scout, who was related to Boone by marriage. There are so many mountain men, cowboys, and other frontier figures, but Boone is the original.

He influenced the Romantic Movement and influenced the way we think about nature. The last chapter of my biography includes quotes from Emerson and Thoreau and Whitman, showing that the type of the frontiersman, not by name, but the type, soon became a part of American culture. The same is true of Crockett; you can find quotes from all three great New England writers that are clearly based on the image of either Boone or Crockett. Whitman actually writes about the Alamo and the Goliad Massacre, but this was a discovery for me. This romantic idea of the West. The forests. The idea of the frontier hero is built around Boone. Byron wrote about him. The Filson biography influenced Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Before Daniel Boone, the wilderness was thought of as a bad place. The forest was evil, a threat. The Indians were there, and it was a place the colonists wanted to clear up. Boone is a figure who loved the wilderness, the mother world of the forest, and loved this middle ground between civilization and the Indians. He's the original. He's at ease with the Indians and with nature. He's friends with the Indians. He doesn't fight the wilderness. He believes in preserving it, even though he's leading people in to clear it up, in effect destroying it. I think he realized that later in life. He’d helped to destroy the hunting ground. But he was almost an Indian himself. He was once adopted by the Shawnees.

In my reading, I believe I saw that you knew you were getting into a very crowded field, when you wrote your biography. Many believe that John Mack Farragher’s biography of Boone published in 1992 is among the best Boone biographies. Your biography was published in 2007. Did you have any thoughts or concerns about “writing in his shadow” or whether there might be a lot of comparisons to his publication?

I believe that Faragher’s biography was among the best. I think there are two or three reasons. He's the first Boone biographer I know who really used the Draper Collection definitively.

He was the first Boone biographer who had that much interest in the Indians and demonstrated a lot of knowledge about them. Faragher was very sensitive about Boone’s relationships with First People, and that puts him very high in my mind.

I think I learned something from each of the previous Boone biographies. What I took most from Faragher’s work was his use of the Draper Collection from the Wisconsin Historical Society. In the nineteenth century Lyman Draper spent his life collecting documents and interviews about the American frontier. His collection is an ocean of papers, some in handwriting almost unreadable. The archive is a treasure trove, and Faragher and others showed me its importance. An interview Draper did with Boone’s son Nathan out in Missouri in 1851 contains much of the essential information we have about the subject.

I found it was important to check every source, every quote. An example would be a letter found in an earlier biography, supposedly a letter written by Boone from Boonesborough in 1775 just as they were building the fort. When I tracked down that letter in Lexington, it was just a typescript, with no original. I should have known it was a fake, because if you know Boone's voice, you would know that Boone doesn’t sound like that. That's not the way he talked. Especially at that time when he’s really trying to build a fort with these people who would not cooperate. They're going out on their own. And that's a very, very tough time. Not only that, but the Indians are also attacking. Boone and his men are living in chaos to some degree. But in the fake letter Boone claims all is going well.

His boss, Richard Henderson, was just staying drunk. There are many incidents where somebody else was officially in charge. But Boone was really in charge. He was the person who had to give the orders. When something had to be done, they turned to him. Everybody looked to him.

Boone just had that leadership ability and was able to use that authority effectively, for example, when Blackfish, in the siege of Boonesborough in 1778, said to Boone that you promised that you're going to surrender the fort. Boone explained he’s no longer in charge – somebody else is in charge. They're very good diplomats – Boone and Blackfish. They're very good actors and good diplomats. Boone was a clever negotiator, and in a way, he learned that from Indians. It was very hard to negotiate with Indians, because they’d claim nobody was in charge. The British or somebody tried to negotiate with the great Chief Attakullakulla. “I'm just Chief of an Overmountain Town, and you know I don't have the authority to do that.” Everybody knew he was in authority.

That, by the way, was passed down to Abraham Lincoln. He was born on the frontier, and he learned that. So, he's in Washington. He's the president. But you know, it's Seward and all these people who ask: “What is your policy? What do you call it?” Lincoln says, “My policy is to have no policy.” Playing that game that Indians and others have played on the frontier. New England educated people didn't know what to do with it. This is one of the ways Indians influenced our culture. There are also many other ways.

The Native American culture was probably a much smarter, better culture in some ways than our own today. They have a lot we could have learned from, but we still have people that won't even consider that, because it's the wrong race. Better leaders inspire us to think that better things are possible. When I was interviewed after the Oprah appearance in 2000, I said, “Good leaders make people feel confident, and bad leaders make them afraid.”

Many writers appear to have periods of time where they struggle to write new material, which is commonly referred to as “writer’s block.” Do you experience this, and, if so, what do you do to get through this?

I don’t have writer’s block, since I write in several genres. It’s a matter of switching back and forth. I’m never at a loss for something to write about. If I hit a block, I begin to work on something else for a while and then later switch back.

Your Boone biography could have ended without your last chapter entitled “Across the River into Legend.” In writing it, you obviously draw on your career as a poet, novelist and English professor. For whatever it’s worth, I believe it’s a beautiful evaluation and analysis of the effect Boone’s life had on writers, painters and poets. Why did you choose to include this as the ending of your biography?

Well, that's Boone’s story continued. These frontier people had an enormous impact on the way the nation thought about itself. I also knew about these authors, had spent years teaching them, reading about them, thinking about them. So, I thought it was something I could do that maybe a lot of other biographers couldn't have done. It's important to the way we think of ourselves to this day: we may be living in the suburbs but really think we’re the kind of people that have a place in the country. We still have a foot in that former world, and, for better or worse, that's what it means to be an American. I keep being surprised by the tenacity of that self-image, national myth. Working on [a book about] Crockett, for instance, and thinking about Walt Whitman. I can see that Walt Whitman is deeply influenced by frontier humor. The hyperbole. The exaggeration. I could imagine Walt Whitman “fighting a barrel of wild cats.” The bragging is like a passage from Huckleberry Finn. “I was weaned on kerosene. My hands are deadly. I can grab the tail of a comet. I can walk the Mississippi on stilts.” Here's Whitman, a high romantic and serious poet clearly taking something from the frontier humor of the Old Southwest. I had never realized that until I was reading about Crockett, who's so closely associated with the humor of the Old Southwest. Here’s Walt Whitman, the great romantic epic poet, but he’s also clearly connected to frontier humor.

Are you going to include this in your book about Crockett?

I certainly am. The last chapter will be very similar to the ending of the Boone biography. I quote Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, plus William Faulkner. Here's the great bear hunter and this mythos that Faulkner talks about. And now the wilderness is going, if not gone. We have this great romantic mythos of the bear hunter. But you would be amazed by what you can find in Ralph Waldo Emerson to echo David Crockett about going to the West. Going to the Southwest, and, of course, Thoreau writes exactly the same thing about exploration, about the ownership of land. I was astonished. I went back and read Walden many times, expecting transcendentalism, and I found these sentences that are so clearly about the frontier mythos. Living at ease with the Indians and the sense of nature and relish in solitude. There's a chapter in Walden called “Solitude.”

I even wove this into a biography of Edgar Allan Poe. Poe’s not just a writer of horror stories. He can write beautifully about nature and solitude in nature. This may be very much disapproved of by some Poe scholars, because they want to see Poe only as a writer of gothic horror. He was an American. He was a rival of Emerson, but he was deeply influenced by Emerson, and the last ten pages of “Eureka” are an essay on cosmology that could easily be a paraphrase of much from Emerson and even more from Walt Whitman. “You want to find God. Look into yourself.” That's exactly what Emerson says in his Divinity School Address. Walt Whitman proclaims, “Turn the priest out. I’m here now.” This is high American Romanticism. Edgar Allan Poe can do it. He can do horror and the poetry of nature. Poe may have the greatest range of any American writer.

Some people, as they get older, consider what their legacy might be. As a University Professor and prolific writer, do you ever consider or reflect on what might be your legacy? If so, are you willing to share it with me?

It’s impossible to know. You have no idea what people will be looking for in fifty years. Twain said immortality is fifty years. Some of my poems might be remembered. The hardest work I've ever spent on writing, and possibly the best, certainly the best expository writing I’ve ever done, is in Boone. When I go back and look at the biography, I say, you know that's not too bad. I put everything I’d learned from writing poetry, texture of words, cadence of sentences, compression of language, and writing fiction, narrative dynamics, character study, tension, and the sense of unfolding story, in the life of Boone. I could not have written Boone: A Biography, had I not written the other books, and earlier essays.

I was very lucky to pick Boone at that time. It was a good period in my career. I was ready to tell the story of Boone. I've never had a period in writing more intense. Gap Creek was intense, but that was like six months or so. A very different kind of writing. I was writing in the voice of the character, an uneducated person. Just hearing that voice is a very different thing from expository writing.

As a creative writer I could do some things other biographers hadn’t done. I imagined Boone making the decision to stay in Kentucky in the second year when logically he would go home and put in a crop for his family. The Boone death scene could be out of a novel yet stays with the facts. Many writers wouldn’t do that. Yet those are the places that readers often enjoy most.

This is the end of my interview.

Once the interview was finished, I thanked Mr. Morgan and gave him two bronze coins with images of Daniel Boone on them. He seemed appreciative. I have in my collection three hardbound copies of his Boone biography, so I took one with me and I asked him to autograph it along with my hardbound copy of his book Lions of the West, which is considered a sequel to his Boone biography. When he asked to whom he should autograph it, I asked for only his autograph. He mentioned that many people don’t want an inscription, because they can resell a book for more with an autograph. I smiled and said that I plan to keep it in my collection, but shared a comment made years ago to me by man of letters, author, and Duke University professor Reynolds Price. When I previously presented to Mr. Price three of his novels for autographs with no inscription, he looked at me and said, “Oh, you’re one of those who wants to make money by reselling autographed books.” I disagreed and still have Price’s novels in my collection.

I then requested a photo of the two of us together, since The Boone Society urged me to do so. We posed in front of a bookcase where I made sure one could see the spine of Robert Morgan’s Boone biography between us.

It was now noon. In order to help his busy day go a little more smoothly, my wife brought in lunch from a nearby restaurant, so Mr. Morgan and I and our wives could enjoy a quiet and private lunch. He continued to discuss his work about Boone but also revealed and discussed additional writing projects on which he was working.

We finished lunch, and at one o’clock, there was a knock on the library door. It was a videographer from “Surry on the Go” indicating he was there to interview Mr. Morgan, so I helped guide him to a corner of the Museum where he could conduct an interview. We said our goodbyes to Nancy Morgan, and my wife and I cleaned up the library table. We proceeded to the second-floor auditorium where there would be a reception for Mr. Morgan, he would autograph books, and his presentation on stage would begin at three o’clock.

It was two o’clock, and premium ticket holders began filing into the auditorium. Tickets were collected at the door in exchange for a paperback copy of Morgan’s Boone: A Biography. It’s now only available in hardback through specialty booksellers. A line formed in front of a table where Mr. Morgan was seated and he signed books, posed for photos and spent time chatting with all who wanted to meet and engage with him. I used my time taking photos, talking to friends and meeting people who were excited to be at this event.

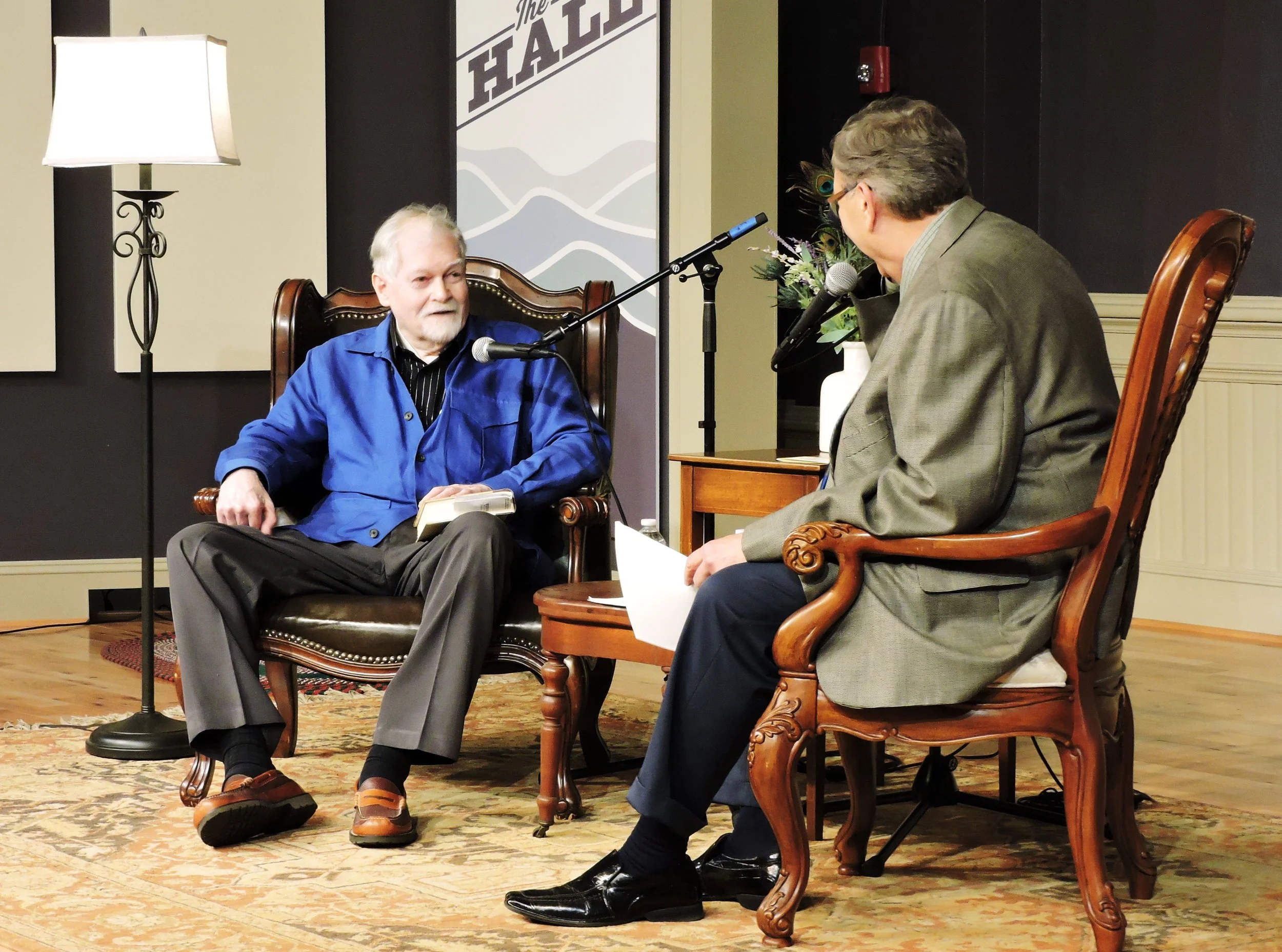

When the appointed hour of three o’clock arrived, people took their seats in a room set up in rows facing the stage. A head count showed there were ninety-two people in the room. I found a seat next to my wife on the right in the first row. We sat there, so I could take notes and come and go with a camera to take photos without disrupting anyone’s view. Mr. Morgan was escorted on stage.

The stage was set with two large comfortable chairs set on an oriental rug. There were two small tables in between the chairs along with a microphone on a stand, and a floor lamp was standing to the right. Mr. Morgan got comfortable in the chair on the left, and Mr. Carl White sat in the chair to our right, and he was planning to interview Mr. Morgan for the next hour.

Mr. White is a broadcaster who hosts the television series Life in the Carolinas. He’s also the creator and host of Life in Wilkes, which is an online series dedicated to the stories of Wilkes County, North Carolina. I took a few more photos and then pulled out my note pad and pen to begin taking notes. In order to not repeat Mr. Morgan’s responses in my interview, the remainder of this article is a summary of Mr. Morgan’s responses to Mr. White’s questions that focus on Daniel Boone.

Morgan used everything he knew about writing to tell the story of Boone, and his background in poetry and storytelling helped him write this biography. When he wrote Brave Enemies: A Novel of the American Revolution in 2003, it led him to writing the biography about Boone. Morgan said about his writing that, “You have to make the reader feel that this story is going somewhere.”

He indicated that Boone’s reputation grew when he was a teenager. He was charismatic and the center of social life. Boone was always seeking the white world but liked being in the wilderness.

While in North Carolina, Boone spent time with the Catawbas and the Cherokee, and he had his foot in two worlds. He learned young not to be too good in a shooting competition with the Indians. Boone understood and had great sympathy toward everyone, including Indians.

North Carolina is where Boone became who he really was. “North Carolina is the place where he became Daniel Boone.” He also really liked Missouri, because the Indians were there. Boone liked whites, the Indians, the wilderness and hunting.

In 1775, Boone wrote a law that there should be “No wanton killing of game.” He understood the destruction of game.

Boone’s character stands up well today, but he was always in debt. This is true of all frontiersmen, because they were all optimists. They had hoped and thought all would go well. We live in a very different world today, but the issues of character are the same.

Boone’s relationship with the Indians was very complicated. Indians define people by likeness, and whites define people by difference.

After Mr. White’s interview, attendees were permitted to come forward to a mic and ask questions. Some of Mr. Morgan’s responses are as follows:

Boone loathed Kentucky after losing everything. He felt betrayed.

I wanted to get a feeling about Who was Daniel Boone? A good teacher of history is a storyteller, and one brings history alive by making it interesting. You’re telling a human story to humans.

The last question was from a young lady who wanted to know how to become a full time professional poet, and Morgan’s response was, “Be persistent. You don’t have to read a specific thing. You have to read everything!”

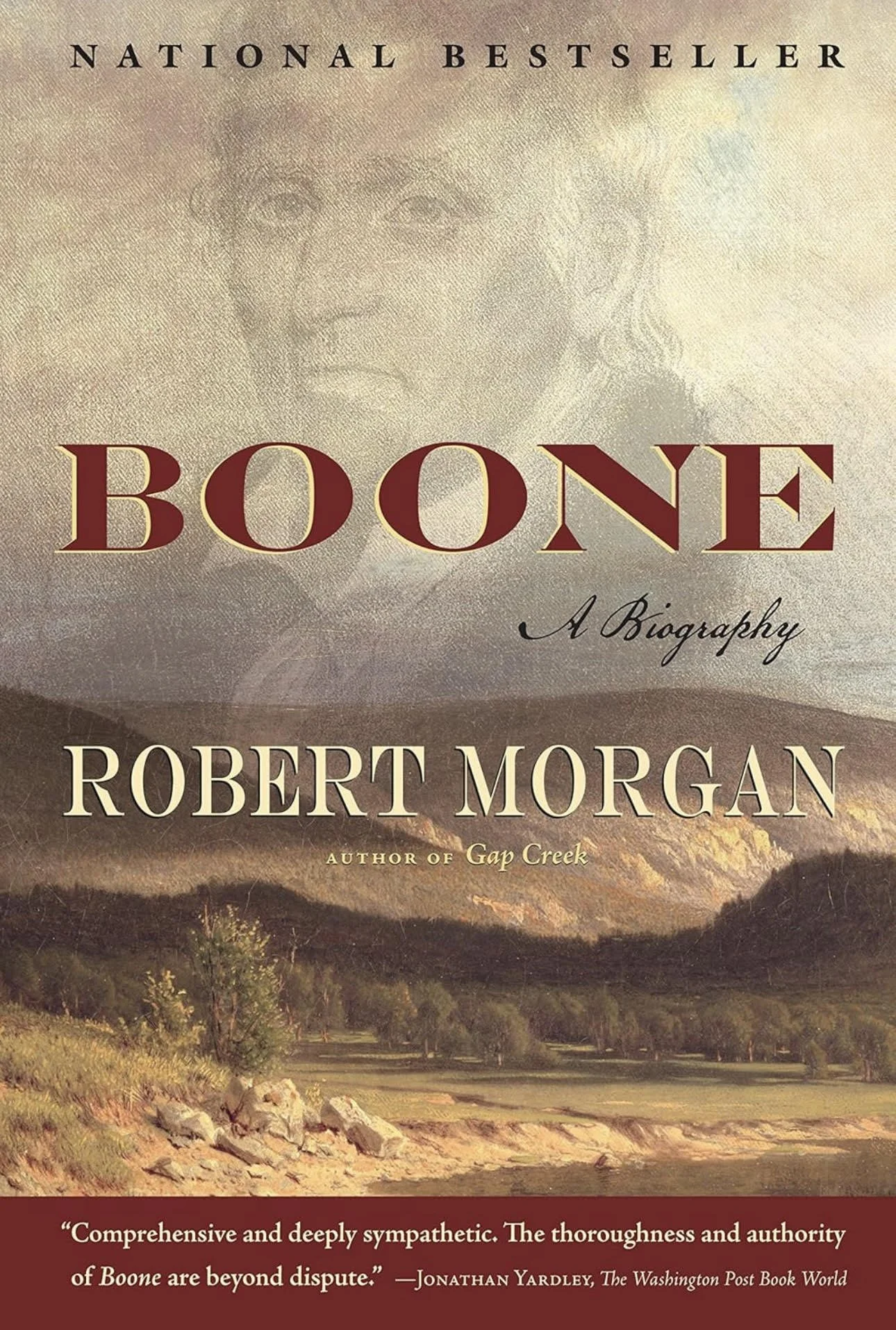

Boone: A Biography by Robert Morgan- Book review by Robert Alvin Crum copyright 2025

Hardback – Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2007 – 538 pages

ISBN: 978-1-56512-455-4

Paperback – Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008 – 538 pages

ISBN: 978-1-56512-615-2

The publication of this biography is relatively recent, so it’s easy to find it in paperback, and the hardback copy can be found online with some booksellers. It’s included in The Boone Canon due to the high quality of research, analysis of Boone’s life and character, and the style of the author’s prose.

Robert Morgan was born in 1944 in Hendersonville, North Carolina. He spent his childhood on the family farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. As a child, he began writing poetry, fiction and composing music. After beginning to study engineering and mathematics at North Carolina State University, he transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He also changed his course of study to English and graduated in 1965 with a Bachelor of Arts. Morgan then attended University of North Carolina at Greensboro and graduated with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1968.

Initially, Morgan’s publications were short stories, but he quickly switched to writing poetry. When he began teaching at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, he wrote and focused on poetry for ten years. Many prestigious poetry and literary awards followed.

It is also important to look at the Introduction of this book to learn about what led him to write this Boone biography. He was born in the mountains of western North Carolina and spent his time hunting, trapping, fishing, and hiking the mountain trails. During his childhood, Morgan listened to stories about “the old days” while sitting on the porch or in front of the fireplace. He was connected to the past, the Indians, and the early frontier. He writes that his father was a wonderful storyteller who “had a lifelong interest in Daniel Boone and loved to quote the hunter and explorer.” His father also thought that Daniel Boone’s mother, Sarah Morgan, might be related to them. Robert Morgan writes that he “always felt a kinship with the hunter and trapper and scout.”

Much has been written about Boone, and frequently one must wade through what is myth or fact. Morgan works to find what was factual and mentions that Boone is a much more complex person than he noticed before his research. Recently I was blessed with the opportunity to interview Robert Morgan who advised that he spent three years intensely researching this biography. He added that he completed all the research for this book himself, because he loves research, and he did not use any research assistants.

Morgan observes in this biography that, “Of major figures in early American history, only Washington and Franklin and Jefferson have had their stories told more often and in greater detail.” In his research for this book, he explores what it was about Boone “that made him lodge in the memory of all who knew him and made so many want to tell his story.” Morgan wants to know and then shows us how such a common man that was a scout and hunter “turned into an icon of American culture.”

I believe it’s important to know about Morgan’s career as a poet, novelist and English professor to better understand the style and focus of his Boone biography. Morgan uses his vast knowledge of poets and men of letters, especially in his last chapter “Across the River into Legend.” In this closing chapter, he describes Boone’s influence on writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. Morgan shows us how these writers, and even painters, were influenced by Daniel Boone’s life in creating the High Romantic Movement of the nineteenth century.

Morgan’s attention to detail reveals the events of Boone’s story with the accuracy of a historian and a biographer; however, there’s more. Using the prose of the poet that he is, Morgan peels back the many layers of Boone as a complex man to reveal why this “common man” became an American icon.

I highly recommend this book for two reasons. Morgan’s intense research provides an accurate and meticulous biography about Boone. Secondly, his experience and expertise as a poet, novelist and English professor provides a well-written analysis of Boone’s life and personality as the “original frontiersman” who demonstrates, even today, what it means to be an American.